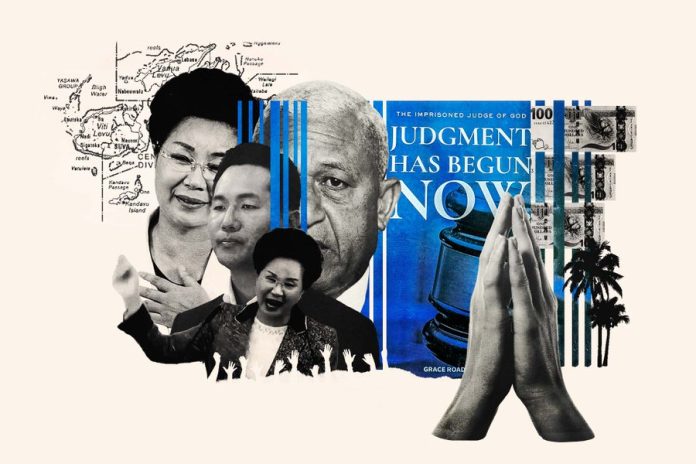

By Aubrey Belford (OCCRP), OCCRP Pacific, Hyein Kang (KCIJ-Newstapa), and Myungju Lee (KCIJ-Newstapa)

Grace Road Church believes a nuclear-tinged Judgment Day is rapidly approaching — and that Fiji is the post-apocalyptic promised land from which they’ll feed humanity. But despite repeated accusations of abuses, including ritual beatings and forcing members to perform unpaid labor, they’ve received a warm welcome from the Fijian government.

Key Findings

*Grace Road Church, an apocalyptic Christian sect from South Korea, moved to Fiji and built a flourishing business empire.

*The group’s leader is in prison in South Korea for abusing its adherents, and former members describe being beaten and made to work without pay.

*Though a police investigation into other sect leaders accused of abuse is still open in Fiji, no charges have been filed.

*A top prosecutor says there’s not enough evidence — but reporters found that the Fijian police in fact interviewed witnesses who gave them key information.

*The group is widely seen as enjoying the favour of Fiji’s authoritarian government. It has been lauded by Fiji’s powerful prime minister and received millions in loans from the state-backed Fiji Development Bank.

In August 2018, a team of 17 South Korean police officers flew to Fiji on a secret mission: to take down the leaders of a Christian doomsday sect accused of taking away its adherents’ passports and subjecting them to ritual beatings.

The roughly 400-strong group, known as the Grace Road Church, had moved to the Pacific Island nation from South Korea several years earlier. Under the charismatic leadership of Reverend Ok-joo Shin, they came to believe the world was heading for nuclear war and that Fiji’s tropical islands would be a safe haven where they could carry out their “unprecedented biblical reformation” to revive Christianity.

Reverend Shin — who styles herself the “Spirit of Truth” — had been arrested at Seoul’s main airport just a few days earlier as she arrived to visit her homeland on charges including assault, child abuse, and imprisoning church members.

Now, having assembled in Fiji, the South Korean officers teamed up with local law enforcement and began combing through the sect’s properties, starting with a night-time raid on their sprawling green farm on the south coast of the country’s main island. Over two days, the joint force arrested six members, including Shin’s son and second-in-command, Daniel Kim.

In one room on the farm, they came across a drawer containing dozens of passports — what seemed like clear evidence that the group was controlling the movements of its adherents.

But, almost immediately, the operation fell apart. Within days, a Fijian court blocked the church members’ deportation to South Korea. Fijian police then called their Korean counterparts and told them they would take over the investigation.

The Grace Road members were released, and the Korean police flew back to Seoul empty-handed.

“When we heard from the Fijian police that they had to release the suspects, I didn’t understand what was going on,” said one South Korean officer who took part in the operation, but declined to be named because he is not authorized to speak to the media.

The failed attempt to decapitate the sect proved to be a turning point. In the ensuing years, Grace Road has not only thrived as a religious group — it has also flourished as a commercial juggernaut. While Reverend Shin now sits convicted in a Korean prison, her son Daniel Kim has built the church’s businesses into a rare bright spot in Fiji’s pandemic-hit economy, though he remains the subject of a Korean arrest warrant to this day.

He has done so thanks in part to a warm welcome and financial support from Fiji’s repressive government, headed by long-serving prime minister and former armed forces chief Frank Bainimarama. That support includes at least FJ$8.5 million (US$3.8 million) in loans from the Fiji Development Bank, a state-backed institution set up to develop the country’s economy, a joint investigation by OCCRP and the Korea Center for Investigative Journalism (KCIJ-Newstapa) has found.

The bank ultimately reports to Fiji’s second-most-powerful politician, Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum. Often called the “Minister for Everything,” he is the second member of an unofficial governing tandem with the prime minister, serving as the country’s attorney general and holding several other ministerial portfolios.

Thanks in part to the government loans it received, Grace Road’s businesses are ubiquitous in Fiji. The sect now operates the country’s largest chain of restaurants, controls roughly 400 hectares of farmland, owns eight supermarkets and mini marts, and runs five Mobil petrol stations. Its businesses also provide services such as dentistry, events catering, heavy construction, and Korean beauty treatments.

Grace Road’s business empire depends in part on the unpaid labor and financial contributions of its hundreds of devotees, some of whom have sunk all of their wealth into the church, according to former members and Korean authorities. Other abuses have also continued, including restrictions on followers leaving Fiji and regular ritual beatings for transgressions.

Fiji’s government has assured the South Korean police and the people of Fiji that they would pursue the case, but have not pressed any charges against Grace Road Church. Though they traveled to South Korea as part of a joint investigation following the 2018 arrests, police did not find enough evidence to justify prosecution, Fiji’s independent director of public prosecutions, Christopher Pryde, told OCCRP.

However, OCCRP and KCIJ-Newstapa were able to establish that, on their trip to South Korea, Fijian officers in fact spoke to key witnesses — who described beatings and other abuses they allegedly suffered at the hands of some of the very same sect members who had been arrested and let go in 2018.

Though Grace Road is a prominent presence in Fiji, criticism of the group is often muted due to laws that stifle free speech and encourage self-censorship in the media. Opposition figures and independent outlets have raised concerns about the government’s perceived closeness to the sect, but few details have emerged.

Support from Fiji’s powerful prime minister and attorney general makes the sect a “protected species” in the country, according to Graham Davis, a long-serving government spokesman who recently left Fiji and became a critic of its rulers.

“The real reason why they were being allowed to stay there was because they were a principal form of economic activity in the country,” said Davis, who now lives in Australia. “[The government] didn’t seem to have any concern about the fact that unlike local businesses, these people had, effectively, slave labor.”

“I specifically went to the attorney general, Aiyaz Sayed-Khaiyum, and said, ‘look, this is not a good look for the country. Why are these people being allowed to do what they’re doing?’ And the answer that he gave me was to brush it off and say, ‘Well, they make good ice cream.’”

Prime Minister Bainimarama, Attorney General Sayed Khaiyum, Fijian immigration, Fiji’s investment promotion agency, the Fiji Development Bank, and the Fijian police did not respond to questions sent by OCCRP and KCIJ-Newstapa.

Grace Road Church and ExxonMobil also did not respond to questions.

The Pleasant Land

In Grace Road’s own telling, the group’s relocation to Fiji in around 2013 was motivated by their belief that a global famine would be an inevitable part of the coming cataclysm. According to the group, Fiji’s verdant isles are the “pleasant land” foretold in the Bible, that will serve as “the throne that God has established for judgment.” The group’s Fijian businesses would prepare to feed a starving world.

American Dream Deferred

In the early 2010s, Reverend Shin and a number of followers moved to New York and swiftly tried to establish their bona fides by performing a miracle of spiritual healing, according to allegations leveled by the conservator of the estate of Seungick Chung, the brother of a Grace Road devotee.

Chung, who suffers from paranoid schizophrenia and seizures, was brought from Connecticut to New York by his sister, a member of the church, in late 2012. Taken off his medication, Chung soon had a psychotic episode and began wandering the streets. He was taken back home and had a sock stuffed in his mouth and was duct-taped to a piece of furniture by his wrists, ankles, and knees at Reverend Shin’s direction. He later developed gangrene and had his right leg amputated above the knee.

Grace Road soon abandoned its American outpost. Chung’s sister and her fiance were reportedly convicted of reckless endangerment in 2013 and sentenced to a year in prison. In September 2018, a federal court in New York ordered Grace Road Church and Reverend Shin to pay Chung’s estate US$3.95 million in compensation for “false imprisonment, intentional infliction of emotional distress, assault and battery, and punitive damages.”

“We’ve been trying to collect on this judgment in Fiji,” said Sung-ho Hwang, the lawyer for Chung’s estate. “And we’ve been encountering lots of problems. Nobody essentially will take our case.”

MoreLess

In keeping with this vision, Grace Road established a farm in Navua, around 45 minutes west of the capital, Suva, in 2014. It soon opened a network of restaurants and stores that is still expanding today. In an island country where the food sold in stores can be of poor quality, Grace Road has become a significant purveyor of organically grown rice, vegetables, fruit, dairy, and meat. Today, the church makes products ranging from artisanal soaps to frozen chicken nuggets, fresh bread, and custom cakes for special events.

In public, Grace Road presents a friendly face — and one that is everywhere. Grace Road’s stores and dozens of restaurants have become a mainstay of Suva’s shopping centers. Its businesses are now studded around the main southern road of the largest island of Viti Levu and in the western tourism hub of Nadi. Recent developments include a hangar-sized hypermarket near its Navua farm, and another large supermarket in Veisari, closer to Suva.

The sect’s stores are usually clean, modern, and brightly lit, and its new business openings regularly receive glowing write-ups in pro-government media outlets. The staff inside typically comprise a mix of ethnic Korean church members and Fijian employees.

The only discordant note in their sunny branding can be found in a corner at many stores, where English-language pamphlets proclaim “judgements” issued from prison by Reverend Shin. While enjoying a cappuccino and a croffle (a sweet combination of croissant and waffle), customers can read about how the COVID-19 pandemic represents God’s punishment for Reverend Shin’s persecution by Korean authorities, or about the “7-Year Great Tribulation” that will soon strike the earth.

Citing the Old Testament’s Book of Zechariah, one pamphlet warns: “Their flesh will rot while they stand on their feet, and their eyes will rot in their sockets, and their tongue will rot in their mouth.”

“You Get Hit Relentlessly”

Grace Road’s businesses employ several hundred Fijian workers who are paid regular wages. But the sect also owes at least part of its success to countless hours of unpaid labor performed by its members.

Reporters spoke to five former sect members who described an austere life of unpaid work, limited freedoms, and regular violence. Their accounts match the picture painted at Reverend Shin’s trial in South Korea, in which a court found widespread abuses, including ritual beatings of acolytes that happened “almost every day.”

“We just sleep, eat, work, and go to the toilet,” said Yong-rin Kim, 62, who managed construction work for the church in Fiji between 2014 and 2020 before deciding to flee after undergoing a ritual beating.

Grace Road acolytes typically live together on the sect’s farm or on its other properties around Fiji. In Kim’s case, that involved being separated from his wife and sharing a room with six or seven other men. He and the others typically woke at dawn and worked until the early hours of the following morning, six days a week, the labor broken up by evening worship.

Stepping out of line could easily lead to “threshing,” as the group terms its practice of ritual punishment by public slapping and beating.

“When you do something wrong, if you even make a slip of the tongue, you’ll get in trouble. If you rub the leader the wrong way, you get hit relentlessly,” he said.

Grace Road has defended threshing as “spiritual warfare for the salvation of souls” that is set forth in the Bible.

Money contributed by devotees has also been key to the church’s ability to establish itself in Fiji.

On paper, many of Grace Road’s members are investors in its Fijian business empire, and are listed in Fiji’s company registry as shareholders in at least nine locally established companies.

Former members say they had no control over how their money was spent, and often did not even know in which companies they were shareholders.

“No one knows which company is theirs,” said Yoon-jae Lee, a former member.

By examining company documents, reporters were able to determine that at least 339 Grace Road members have been listed as shareholders of the church’s Fijian companies — bringing at least FJ$22.53 million (US$10.24 million) into the country’s economy as capital investment. The ownership of each of the church’s nine companies is typically split among several dozen members, each contributing at least FJ$ 50,000 (US$ 22,730). One person is listed as a director for every company: the church’s de facto leader, Daniel Kim.

This unusual arrangement had the happy effect of enabling Grace Road to obtain investor visas for scores of its acolytes, allowing them to settle in a country where obtaining work permits and residency can otherwise be an arduous process, former government officials and sect members told OCCRP and KCIJ-Newstapa.

“Being a shareholder doesn’t mean anything at all. It is just a tool to get working visas,” former member Lee said.

“There’s No Other Company That’s Treated Like Them”

Grace Road’s dream run in Fiji is also down to a remarkable level of support it has received from the government of Prime Minister Bainimarama.

In 2017, Bainimarama shared a stage with Daniel Kim to hand him the “Prime Minister’s International Business Award.” Last October, the prime minister spoke at the opening of a new Grace Road supermarket and cut the ribbon with Kim — who officially remains under police investigation in both Fiji and South Korea.

“Your enterprises are of uniform high quality and appearance, in operation and efficiency, and I believe you are raising the standard for local retail and restaurant establishments,” Bainimarama said.

Such public shows of support carry a lot of weight in Fiji, where the prime minister wields vast executive authority.

Since coming to power in a 2006 coup, Bainimarama has held onto the role thanks to a system that combines regular democratic elections with episodes of repression. He directly oversees foreign affairs, immigration, and a board that controls the leasing of indigenous land, including where some of Grace Road’s farming operations are located. As a former armed forces chief, Bainimarama is also widely believed to closely control the police, which falls under the defence ministry.

“The PM’s instructions are the instructions of the Almighty. What the PM wants, the PM gets,” Davis, the former government spokesman, said. “In the entire running of the country.”

Grace Road has offered support to Fiji and its government in return. In 2016, the sect rebuilt homes destroyed by a tropical cyclone. The following year, its construction arm renovated the official residences of the prime minister and president, projects for which FJ$ 6.78 million (US$3.1 million) was budgeted. It is unclear how much Grace Road earned from the projects. The Fiji Procurement Office did not respond to written questions about the tender process.

Rival business people grumble privately that, while they struggle with onerous planning and approval processes, the sect’s businesses seem to sail through with ease.

Grace Road’s relationship with the government is “on a totally different level,” a senior executive at a major retailer, who declined to be identified out of fear of government retribution, told OCCRP. “They’re on the highest level you can get. There’s no other company that’s treated like them.”

“A lot of people in Fiji don’t like them but they’re scared to talk about it. Everybody’s scared.”

But though complaints of preferential treatment have circulated, it has not been reported until now that, virtually since the beginning, Grace Road benefited from loans handed out by the state-backed Fiji Development Bank (FDB).

Starting in 2015, the group’s agricultural arm has been loaned at least FJD$ 8.51 million (US$4.25 million) by the FDB, according to mortgage and property documents reviewed by reporters. Since such documents only show loans made with real estate as collateral, the total amount of money loaned by FDB may be higher.

Former government spokesman Davis said such loans would have had to be cleared with his former boss, the attorney general, to which the FDB reports.

“There is no way in the world the Fiji Development Bank would be lending money to Grace Road without the official imprimatur of the AG [Attorney General] Sayed-Khaiyum. No way.”

“Why Did They Ignore My Victim’s Statement?”

Reporters also found apparent serious shortcomings in the Fijian police investigation into the group, which followed the earlier arrests of six Grace Road members, including de facto leader Daniel Kim, in August 2018.

According to local media reports, they were released after a local court temporarily blocked their deportation.

But in written responses to questions, the South Korean police said that the Fijian police had released the Grace Road members after a high-level meeting that included Fiji’s late immigration chief, the prime minister’s personal private secretary, the solicitor general, and the country’s top prosecutor. Such a “release through a high-level bureaucratic meeting is unusual,” the South Korean police said.

Christopher Pryde, Fiji’s director of public prosecutions, told OCCRP there was no political pressure behind the church members’ release. “That’s not the way it works here,” he said.

Fijian law enforcement concluded that, since the alleged offenses took place on Fijian soil, they should be investigated and charged there, Pryde said.

He said that he pressed the Fijian police to provide more evidence of alleged mistreatment, but that they have not found any that would justify charges against sect members still residing in Fiji.

“Look at the police docket. There’s simply not enough evidence” he said.

As a result, though the case against the sect members remains open, no charges have been filed, he said.

However, OCCRP and KCIJ-Newstapa were able to determine that Fijian police did speak to key victims who provided statements on alleged abuses.

According to South Korean police, in December 2018 the Fijian police sent a team of five officers to South Korea, who interviewed four alleged victims of Grace Road abuses.

Reporters were able to confirm the identity of three of these people. All three were beaten by sect members who were later arrested and released in Fiji in August 2018, according to the conviction handed down in Reverend Shin’s trial. Grace Road’s second-in-command, Daniel Kim, also took part in the confiscation of one of the victims’ passports and restricted his movements while in Fiji, the court found.

Two of the victims, Yoon-jae Lee and another man who asked to be referred to by his last name, Jung, told reporters they had described to Fijian police having been abused by some of those sect members while on Fijian soil.

Lee said he told Fijian police that he had been beaten, had his passport taken away, and was made to work without pay. Backing up his claim, he provided reporters with a photo he took together with two Fijian police officers in what appears to be a Korean police interrogation room. He said he was ready to testify at a Fijian trial if asked.

“[The Fijian police] came to check the Korean police investigation, the things that we had already told the police in Korea,” Lee said. “They were checking if these things were true and met the victims again… they even recorded it.”

“But then they went back to Fiji, they decided there were no grounds for suspicion,” he said. “Please ask them strongly: why did they ignore my victim statement?”

South Korean police told reporters they had also furnished their Fijian counterparts with additional evidence, including a translation of Reverend Shin’s conviction.

When OCCRP went back to Fijian prosecutor Pryde with this information, he maintained that Fijian police had not been told by these witnesses of any offenses committed by Grace Road members still living in Fiji.

“The ones that left Fiji have complained, but the ones that remain in Fiji have no complaints and say they are happy with their living conditions, their work, and they told us they are contributing to the Grace Road Church and are satisfied with their lives,” he said.

“There is no conspiracy or cover-up here,” Pryde said, adding that Fijian authorities were moving ahead with another case in which four Grace Road members allegedly assaulted a pastor from another Korean denomination.

The South Korean Embassy in Suva declined an interview, citing “the sensitive issues of the matter on Grace Road Church and ongoing Korean-Fijian law enforcement cooperation.”

Research on this story was provided by OCCRP ID. Fact-checking was provided by the OCCRP Fact-Checking Desk.

SOURCE: OCCRP/…PACNEWS