Small island nations across the world are bearing the brunt of the climate crisis, and their problems have been accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has severely affected their economies, and their capacity to protect themselves from possible extinction. We take a look at some of the many challenges they face, and how they could be overcome.

Low emissions, but high exposure

The 38 member states and 22 associate members that the UN has designated as Small Island Developing States or SIDS are caught in a cruel paradox: they are collectively responsible for less than one per cent of global carbon emissions, but they are suffering severely from the effects of climate change, to the extent that they could become uninhabitable.

Although they have a small landmass, many of these countries are large ocean states, with marine resources and biodiversity that are highly exposed to the warming of the oceans. They are often vulnerable to increasingly extreme weather events, such as the devastating cyclones that have hit the Caribbean in recent years, and because of their limited resources, they find it hard to allocate funds to sustainable development programmes that could help them to cope better, for example, constructing more robust buildings that could withstand heavy storms.

The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the economic situation of many island states, which are heavily dependent on tourism. The worldwide crisis has severely curtailed international travel, making it much harder for them to repay debts. “Their revenues have virtually evaporated with the end of tourism, due to lockdowns, trade impediments, the fall in commodity prices, and supply chain disruptions”, warned Munir Akram, the president of the UN Economic and Social Council in April. He added that their debts are “creating impossible financial problems for their ability to recover from the crisis.”

Most research indicates that low-lying atoll islands, predominantly in the Pacific Ocean such as the Marshall Islands and Kiribati, risk being submerged by the end of the century, but there are indications that some islands will become uninhabitable long before that happens: low-lying islands are likely to struggle with coastal erosion, reduced freshwater quality and availability due to saltwater inundation of freshwater aquifers. This means that small islands nations could find themselves in an almost unimaginable situation, in which they run out of fresh water long before they run out of land.

Furthermore, many islands are still protected by reefs, which play a key role in the fisheries industry and balanced diets. These reefs are projected to die off almost entirely unless we limit warming below 1.5 degrees celsius.

Despite the huge drop in global economic activity during the COVID-19 pandemic, the amount of harmful greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere increased in 2002, and the past six years, 2015–2020, are likely to be the six warmest on record.

Climate finance (climate-specific financial support) continues to increase, reaching an annual average of US$48.7 billion in 2017-2018. This represents an increase of 10% over the previous 2015–2016 period. While over half of all climate-specific financial support in the period 2017-2018 was targeted to mitigation actions, the share of adaptation support is growing, and is being prioritised by many countries.

This is a cost-effective approach, because if not enough is invested in adaptation and mitigation measures, more resources will need to be spent on action and support to address loss and damage.

Switching to renewables

SIDS are dependent on imported petroleum to meet their energy demands. As well as creating pollution, shipping the fossil fuel to islands comes at a considerable cost. Recognizing these problems, some of these countries have been successful in efforts to shift to renewable energy sources.

For example, Tokelau, in the South Pacific, is meeting close to 100 percent of its energy needs through renewables, while Barbados, in the Caribbean, is committed to powering the country with 100 percent renewable energy sources and reaching zero carbon emissions by 2030.

Several SIDS have also set ambitious renewable energy targets: Samoa, the Cook Islands, Cabo Verde, Fiji, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and Vanuatu are aiming to increase the share of renewables in their energy mixes, from 60 to 100 percent, whilst in 2018, Seychelles launched the world’s first sovereign blue bond, a pioneering financial instrument to support sustainable marine and fisheries projects.

The power of traditional knowledge

The age-old practices of indigenous communities, combined with the latest scientific innovations, are being increasingly seen as important ways to adapt to the changes brought about by the climate crisis, and mitigate its impact.

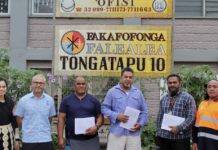

In Papua New Guinea, local residents use locally-produced coconut oil as a cheaper, more sustainable alternative to diesel; seafaring vessels throughout the islands of Micronesia and Melanesia in the Pacific are using solar panels and batteries instead of internal combustion; mangrove forests are being restored on islands like Tonga and Vanuatu to address extreme weather as they protect communities against storm surges and sequester carbon; and in the Pacific, a foundation is building traditional Polynesian canoes, or vakas, serving as sustainable passenger and cargo transport for health services, education, disaster relief and research.

Strategies for survival

While SIDS have brought much needed attention to the plight of vulnerable nations, much remains to be done to support them in becoming more resilient, and adapting to a world of rising sea levels and extreme weather events.

On average, SIDS are more severely indebted than other developing countries, and the availability of “climate financing” (the money which needs to be spent on a whole range of activities which will contribute to slowing down climate change) is of key importance.

More than a decade ago, developed countries committed to jointly mobilize $100 billion per year by 2020 in support of climate action in developing countries; the amount these nations are receiving is rising, but there is still a significant financing gap. A recently published UN News feature story explains how climate finance works, and the UN’s role.

Beyond adaptation and resilience to climate change, SIDS also need support to help them thrive in an ever-more uncertain world. The UN, through its Development Programme (UNDP), is helping these vulnerable countries in a host of ways, so that they can successfully diversify their economies; improve energy independence by building up renewable sources and reducing dependence on fuel imports; create and develop sustainable tourism industries, and transition to a “blue economy”, which protects and restores marine environments.

Fighting for recognition

*For years, SIDS have been looking for ways to raise awareness of their plight and gain international support. As the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) in 1990, they successfully lobbied for recognition of their particular needs in the text of the landmark UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) two years later.

*Since then, the countries have continued to push for a greater emphasis on ensuring that international agreements include a commitment to providing developing countries with the funds to adapt to climate change. An important step was ensuring that climate change negotiations address the issue of “loss and damage” (i.e. things that are lost forever, such as human lives or the loss of species, while damages refers to things that are damaged, but can be repaired or restored, such as roads or sea walls etc.).

*SIDS continue to urge developed nations to show more ambition and commitment to tackling the climate crisis, and strongly support calls for a UN resolution to establish a legal framework to protect the rights of people displaced by climate change, and for the UN to appoint a Special Rapporteur on Climate and Security, to help manage climate security risks and provide support to vulnerable countries to develop climate-security risk assessments.

*SIDS have also advocated for eligibility to development finance to recognise the vulnerabilities they face, including from climate change hazards. The UN will release its recommendations in a report due to be released in August 2021.

SOURCE: UN NEWS CENTRE/PACNEWS