Environmental and social experts from across Asia have called on Japan to refrain from contaminating the sea with radioactive wastewater after it began test running the equipment to discharge toxic water from a crippled nuclear power plant into the Pacific.

The nuclear-contaminated wastewater from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant will contain traces of tritium, a radioactive isotope, and possibly other radioactive traces such as carbon-14, scientists said.

“Nobody wants to dump (radioactive substances) into the ocean,” said David Krofcheck, senior lecturer in the faculty of science at the University of Auckland in New Zealand.

“We need to be aware of the difference between tritium and carbon-14, on one hand, and the radioactive fission products which tend to remain in the human body,” he said, adding that tritium could still enter the food chain throughout its buildup in underwater plants.

“This organically bound tritium still decays with a half-life of 12.3 years, and it stays in the human body for about 10 days, the biological half-life, before excretion.”

Instead of pumping the wastewater into the sea, Japan can dispose of it safely, Krofcheck said, offering an alternative for managing the Fukushima water: to hold it on site in an ever “growing number of water tanks”.

“If the water is properly filtered to leave only tritium and carbon-14, the natural decay of tritium can be used to reduce its radioactivity.

“Since the radioactive half-life of tritium is 12.3 years, holding the water in tanks for seven half-lives would reduce the tritium content to less than 1 percent of its current value.”

This option still leaves the carbon-14 that would still roughly have the same radioactivity because of its 5,730-year half-life, he said.

The potential impact of releasing treated radioactive water from the Fukushima plant into the ocean remains a subject of contention and concern among stakeholders, said Anjal Prakash, clinical associate professor (research) and research director of the Bharti Institute of Public Policy at the Indian School of Business in Hyderabad.

“The ocean release decision itself has sparked opposition, leading to ongoing debates on alternative water management strategies. The decision-making process weighs safety, public perception, regulations and potential impacts on industries and trade.”

While the Japanese government and the Tokyo Electric Power Company, operator of the crippled plant, say there is minimal risk, differing opinions persist, Prakash said, adding that factors such as ocean currents, distance, dilution and treatment efficacy will determine the impact on neighboring areas, including South Asia, Pacific Island countries, Australia, New Zealand and the rest of the world.

Long-term effects and bioaccumulation concerns remain, he said. “Evaluating the precise impact is complex, necessitating considerations of various factors and ongoing scientific research.”

Despite continuing opposition from domestic experts, civic groups and fishery organizations, Japan has been rushing to dump the nuclear-contaminated water into the ocean, which has also spurred protests from neighboring countries and communities within the Pacific Islands.

In April the Fijian government reaffirmed its opposition to Japan’s plan to discharge nuclear-contaminated wastewater into the Pacific Ocean.

Fiji’s Deputy Prime Minister Manoa Kamikamica said earlier that the Pacific Ocean should not be seen as an easy and convenient dumping ground for unwanted and dangerous materials and waste that larger countries produce but do not want to use in their own ecosystem, local media reported.

“The social and economic impact of this irresponsible behavior is catastrophic, particularly on our vulnerable communities,” he said.

Environmental groups have argued that the move sets a bad precedent and poses a serious danger to Pacific communities that depend on the ocean for their livelihoods.

“We have enough man-made disasters,” said Peter Bosip, head of the Centre for Environmental Law and Community Rights in Papua New Guinea.

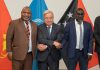

The PNG Prime Minister James Marape, said a day earlier that Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and the previous prime minister Yoshihide Suga have both “assured me that Japan would never allow the discharge of the water until and unless safety has been confirmed by scientific evidence”.

Many people are asking why, if the wastewater treated by Japan’s Advanced Liquid Processing System is so safe, Japanese are not using such water for alternative purposes, in manufacturing and agriculture for instance.

According to a report issued by Tokyo Electric Power Company on 05 June, the radioactive elements in the marine fish caught in the harbor of the Fukushima plant far exceed safety levels for human consumption. In particular, the content of cesium-137, a radioactive element and a common byproduct in nuclear reactors, is said to be 180 times that of the standard maximum stipulated in Japan’s food safety law.

Kalinga Seneviratne, a visiting lecturer at the University of the South Pacific in Fiji, said: “The contamination will affect the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty (adopted in 1986) areas as well when it eventually flows there. Also, since fish stocks are migratory, contaminated fish could be caught within the treaty area.”

If Japan wants to protect a rules-based order, as it says it does, the government should subscribe to the principles of these rules and respect the wishes of the people in the Pacific who argue that the treaty is there to stop something such as this from happening, Seneviratne said.

After being hit by a magnitude-9.0 earthquake and an ensuing tsunami on March 11, 2011, the Fukushima plant suffered core meltdowns that released radiation, resulting in a level-7 nuclear accident, the highest on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale.

SOURCE: CHINA DAILY/XINHUA/PACNEWS