New Zealand is joining a small group of wealthy countries to commit funding to help developing nations facing losses and damages caused by climate change, with an initial pledge of $20 million (US$11.9 million).

The “loss and damage” concept refers to costs already being incurred from climate-fuelled weather extremes or impacts, such as rising sea levels, rather than adapting to future events.

It is a compromise reached between developed and developing countries, as opposed to straight compensation for climate-linked losses after disasters have struck – which rich nations are wary of being seen as reparations for causing climate change and admitting liability.

It is estimated climate change impacts have cost developing countries more than US$800 billion in the past two decades and could rise to between US$500b and US$1 trillion a year by 2030.

World leaders have gathered in Egypt for the United Nations climate change summit COP27 – short for conference of parties – where the internationally fraught concept is officially on the agenda.

Overnight, Germany made the largest commitment so far of US$300m while Belgium announced just over US$4m. Scotland has also upped its contribution to nearly US$14m while Denmark committed US$22m earlier this year.

Climate Change Minister James Shaw said for decades countries most at risk from climate change, including communities in the Pacific, had called on developed nations to “step up and provide support to minimise and address their loss and damage from climate change”.

The negotiations had been “frustratingly slow”, he said, held up by arguments around responsibility for climate impacts and liability.

Shaw, who travels to Egypt for COP27 on Friday, said this announcement was not admitting liability, though he accepted it was “obvious” where responsibility lay.

“Comparatively wealthy countries like Aotearoa New Zealand have a duty to support countries most at risk from climate change.

“The best way to do that is to cut climate pollution, but so too must we support communities to cope with the unavoidable impacts of the climate crisis.

“We know that there are costs associated with loss and damage, we’re going to start contributing to that, even in the absence of a global agreement.”

Historically, developed countries bear the most responsibility for emissions leading to global warming. According to Our World in Data, between 1751 and 2017, the United States, the European Union and the United Kingdom were responsible for 47 percent of carbon dioxide emissions compared to just under 6 per cent from Africa and South America combined.

Despite this, nations have been reluctant to take responsibility for paying for the impacts of that climate pollution.

The “loss and damage” idea originated in 1991 as a sort of insurance scheme against rising sea levels, funded by developed countries in acknowledgment of their historical contribution to climate pollution.

Over two decades later at COP19 in Warsaw, Poland, countries agreed on the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage, but again the issue stalled.

At last year’s UN climate conference in Glasgow, the United States and EU blocked a formal loss and damage financial facility but the “Glasgow Dialogue” was established to enable further discussion over funding.

This year countries have agreed to formally include the topic on the agenda.

Loss and damage funding is separate to the US$100 billion annually by 2020 to help developing countries adapt to the impacts of climate change (so far just over US$140b has been pledged).

Rather, it would compensate costs that countries can’t avoid or “adapt” to. However, there is no agreement yet on exactly what that could entail, such as physical infrastructure through to cultural losses, and what form it would take, for example, a fund with ongoing contributions.

A report put together by the Loss and Damage Collaboration estimates 55 developing nations have suffered climate-related economic losses of over US$800b in the first two decades of this century.

It estimates loss and damage costs could increase to between US$500b and US$1trillion a year by 2030.

Environmental lawyer Teall Crossen said it was great to see New Zealand make this contribution but questions still remained around liability.

“Are we acknowledging that it’s compensation for the damage we’ve caused? Or are we just re-relabelling an existing contribution?

“Pacific countries have been advocating for this before the climate change convention was even agreed.

“They knew there was damage that was going to occur to their islands.

“It’s a principle of international law, that you’re not supposed to harm the environment of other countries. And if you do, you’re supposed to pay reparations.”

Crossen said it had been controversial as countries who had built their wealth and standard of living from burning fossil fuels and emitting greenhouse gases didn’t want to accept liability for them.

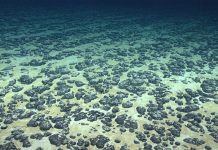

“It’s an enormous tension. You see developed countries, with a high standard of living, built on climate pollution. And then you see, the Pacific suffering from severe droughts, hurricanes, degraded coral systems, that are caused by climate pollution.”

On what could be decided at COP27, Crossen said some of the original proposals were about an insurance scheme with a fund attached to it, contributed to by wealthier countries.

This would allow countries to call on it to repair and/or compensate for damage caused.

“It creates a better power balance. Because they’re not having to go cap in hand to big developed countries for money when they’re hit by a cyclone.”

Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta said New Zealand was “not opposed” to a central fund and it would also look to work directly with Pacific governments.

Ahead of COP, Mahuta said the announcement put New Zealand at the “leading edge” of countries supporting this action, which would support the Pacific in particular.

“The loss of land and resources from sea-level rise is a well-known threat, but loss and damage for Pacific countries take many forms.

“We hear from our neighbours about climate impacts on freshwater systems, plant and animal ecosystems, coastal waters and the ocean.

“It threatens the very basis of their lives. Loss and damage is happening to homes and crops and fisheries, but it also happens to cultures, languages, people’s mental health and their physical wellbeing.”

The $20m comes out of the Government’s $1.3b (US$755 million) climate finance package announced last year to run across four years.

Vanuatu, meanwhile, through which the concept originated, has now asked the world’s highest court – the International Court of Justice – to issue an opinion on the right to be protected from adverse climate impacts.

Such a ruling could carry moral authority and legal weight, strengthening calls for compensating poor nations through loss and damage.

New Zealand is one of 11 nations helping Vanuatu draft its question.

SOURCE: NZ HERALD/PACNEWS