Despite the annihilation of two major Japanese cities in 1945, atomic bombs have not been relegated to the pages of history books, but continue to be developed today – with increasingly more power to destroy than they had when unleashed on Hiroshima and Nagasaki back in 1945.

Those first nuclear weapons deployed by the United States, indiscriminately killed tens of thousands of non-combatants but also left indelible scars for the immediate survivors, that they, their children and grandchildren still carry today.

“The Red Cross hospital was full of dead bodies. The death of a human is a solemn and sad thing, but I didn’t have the time to think about it because I had to collect their bones and dispose of their bodies”, a then 25-year-old woman said in a recorded testimony, 1.5 km from Hiroshima’s ground zero.

“This was truly a living hell, I thought, and the cruel sights still stay in my mind”.

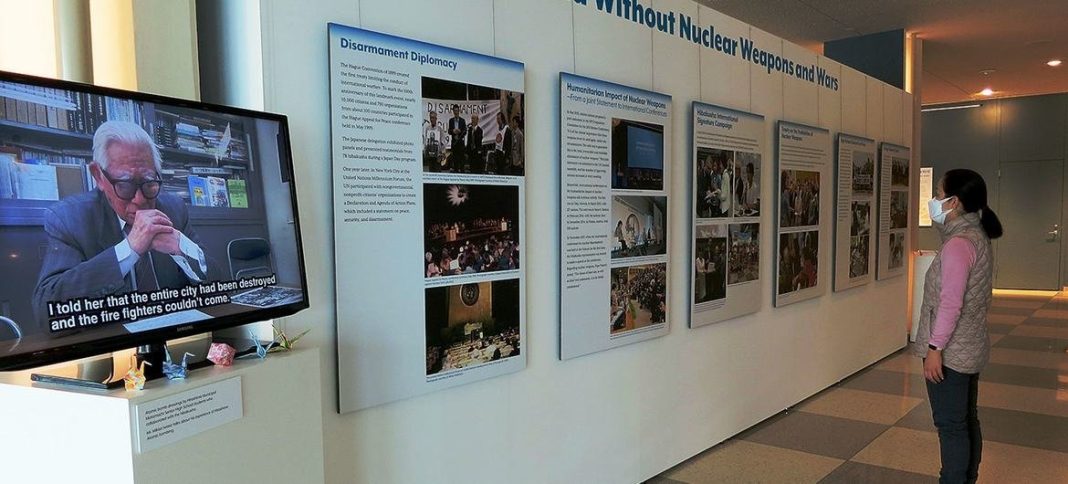

To highlight the tireless work of the survivors, known in Japanese as the hibakusha, the UN’s Office for Disarmament Affairs, created an exhibition at UN Headquarters in New York which has just come to a close, entitled: Three Quarters of a Century After Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Hibakusha—Brave Survivors Working for a Nuclear-Free World.

It vividly brings to life the devastation and havoc wreaked by those first atomic bombs (A-bombs), and their successor weapons, the more powerful hydrogen bombs (H-bombs) which began testing in the 1950s.

Quest to save humanity

In the aftermath of the bombings in Japan, the hibakusha, conducted intense investigations with the aim of preventing history from repeating itself.

With an average age of 83 today, the dwindling band continue to share their stories and findings with supporters at home and abroad, “to sav[ing] humanity…through the lessons learned from our experiences, while at the same time saving ourselves”, they say, in the booklet No More Hibakusha -Message to the World, which accompanies the exhibit.

Recounting the day in Hiroshima that 11 members of her family slept together in an air raid shelter, a then 19-year-old woman spoke of how three small children died during the night, while calling for water.

A shirt shredded in the nuclear bombing was an artefact in the disarmament exhibition.

“The next morning, we carried their bodies out of the shelter, but their faces were so swollen and black that we couldn’t tell them apart, so laid them out on the ground according to height and decided their identities according to their size”.

These brave survivors testify that peace cannot be achieved ever, through the use of nuclear weapons.

‘Absolute evil’

A group of elderly hibakusha, called Nihon Hidankyo, have dedicated their lives to achieving a non-proliferation treaty, which they hope will ultimately lead to a total ban on nuclear weapons.

“On an overcrowded train on the Hakushima line, I fainted for a while, holding in my arms my eldest daughter of one year and six months. I regained my senses at her cries and found no-one else was on the train”, a 34-year-old woman testifies in the booklet. She was located just two kilometres from the Hiroshima epicentre.

Fleeing to her relatives in Hesaka, at age 24 another woman remembers that “people, with the skin dangling down, were stumbling along. They fell down with a thud and died one after another”, adding, “still now I often have nightmares about this, and people say, ‘it’s neurosis’”.

One man who entered Hiroshima after the bomb recalled in the exhibition, “that dreadful scene – I cannot forget even after may decades”.

A woman who was 25 years-old at the time, said, “when I went outside, it was dark as night. Then it got brighter and brighter, and I could see burnt people crying and running about in utter confusion. It was hell…I found my neighbour trapped under a fallen concrete wall…Only half of his face was showing. He was burned alive.”

Uniting for peace

The steadfast conviction of the Hidankyo remains: “Nuclear weapons are absolute evil that cannot coexist with humans. There is no choice but to abolish them”.

In August 1956, the survivors of the 1945 atomic bombs in Hiroshima on 6 August and Nagasaki three days later, formed the “Japan Confederation of A and H-Bomb Sufferers Organisations”.

Encouraged by the movement to ban the atomic bomb that was triggered by the Daigo Fukuryu Maru disaster – when 23 men in a Japanese tuna fishing boat were contaminated by nuclear fallout from a hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll in 1954 – they have not wavered in their efforts to prevent others from becoming nuclear victims.

“We have reassured our will to save humanity from its crisis through the lessons learned from our experiences, while at the same time saving ourselves”, they declared at the formation meeting.

The spirit of the declaration, in which their own sufferings are linked to the task of preventing the hardship that they continue to carry, resonates still in the movement today.

‘Strong, powerful’

The Japanese art director who designed the exhibition at UN Headquarters, Erico Platt, acknowledged in an interview with UN News, that inevitably, the COVID pandemic had reduced the number of people able to see the exhibition in person, as well as prevented elderly hibakusha from participating.

In the past, “at least 10 to 30 [hibakusha] came to do live testimonials at the site as well as outside of the United Nation, like churches, schools”, she said. “But this time because of the pandemic no one could come”.

She also shared another challenge that arose from working with the elderly population, explaining that one of the hibakusha had died, after the exhibition was sent out to be printed.

“I was including him as one of the survivor’s panels but since he died, I had to call the printing company to stop it and modify the text…to the past tense…[leaving] only two weeks for nearly 50 panels” to be produced, she said.

According to his panel, the late Sunao Tsuboi, was studying at the university in Hiroshima when the bomb hit.

“I was blown at least ten meters by the blast…almost all parts of my body were burned. After a week I lost consciousness. It took me over a month to regain [it]”.

Since 1945, Tsuboi had been hospitalized many times for diseases caused by the aftereffects of radiation.

Platt said that she wished there had been more media coverage to “raise some attention”, saying, “I think this is the best exhibit I’ve done. Very strong, powerful but in a way beautiful, I think”.

Push for disarmament

The Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) was negotiated in the late 1960s to promote cooperation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, and to further the goal of achieving nuclear disarmament and general and complete disarmament.

About a decade later, a national delegation from Japan that was calling on the UN to ban nuclear weapons requested the Organisation investigate the damage caused by the atomic bombs used at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the situation of those who survived.

Based on three nationwide surveys of A-bomb survivors and documented work of experts from various fields, the first international symposium on the situation took place in 1977. In addition to putting a human face on nuclear disarmament, the word hibakusha became internationally recognised.

The exhibition lays out that five years later, as the anti-nuclear and peace movement was gaining steam, the United States and Russia tried to deploy tactical nuclear weapons to Europe. The Hidankyo sent a delegation of 43 people to the UN Second Special Session on Disarmament (SSDII).

Speaking up, being heard

Subsequently, hibakusha became more and more vocal in the suffering that was inflicted upon them, hoping that it could help create a road map towards the abolition of nuclear weapons.

In oral testimonies, they shared their experiences both during and after the bombings and sent written messages to the NPT Review Conference in 2010 appealing to the world.

In July 2017, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which complements the NPT, was adopted and came into force last year on 22 January.

In launching the UN’s Disarmament Agenda in 2018, Securing Our Future, Secretary-General António Guterres said, “the existential threat that nuclear weapons pose to humanity must motivate us to accomplish new and decisive action leading to their total elimination. We owe this to the Hibakusha…and to our planet”.

‘Bold steps’ needed

The UN chief said that the world is indebted to the hibakusha for their “courage and moral leadership in the universal fight against the nuclear threat”.

Moreover, the UN is committed to ensuring their testimonies live on, as a warning to each new generation.

“The Hibakusha are a living reminder that nuclear weapons pose an existential threat and that the only guarantee against their use is their total elimination”, Guterres stated. “This goal continues to be the highest disarmament priority of the United Nations, as it has been since the first resolution adopted by the General Assembly in 1946”.

While the Tenth Review Conference of the NPT, which had been scheduled for January, has been postponed on account of the COVID-19 pandemic, he continued to urge world leaders to “draw on the spirit of the Hibakusha” by putting aside their differences and taking “bold steps towards achieving the collective goal of the elimination of nuclear weapons.

SOURCE: UN NEWS CENTRE/ PACNEWS