By Jose Sousa-Santos

The illicit drugs trade in the Pacific Islands continues to evolve despite Covid-19 border closures. The seizure of more than 500 kilograms of cocaine in Papua New Guinea in 2020 demonstrated that the pandemic had not diminished the trafficking of drugs through the region. Destined for Australia, and with a street value estimated at AUD$81 million (US$58.3 million), the seizure emphasised the importance of partnerships between regional law enforcement, in this case the Australian Federal Police and the Royal Papua New Guinea Constabulary. In the same year, a cocaine “ghost ship” containing 649 kilograms of the drug, with a street value of more than AUD$112 million (US$80.6 million), foundered on an atoll in the Marshall Islands. In 2021, 14 kilograms of cocaine washed up on Tongan beaches, its collective street value estimated at AUD$3.1 million (US$22.5 million).

The pandemic has not weakened demand for, or trade in, illicit drugs. This is evident in the growth of local markets and the emergence of a culture of drug abuse among the Pacific’s youth. Statistics recently released by Samoa’s Ministry of Police and Prisons show a spike in drug-related arrests and that, disturbingly, 96 percent of those arrested were first-time offenders. This reflects a trend that is in part exacerbated by the socio-economic fallout of the pandemic.

The region’s vast and porous maritime borders, weak jurisdictions and limited enforcement capabilities are key structural challenges and enablers to transnational crime in the region.

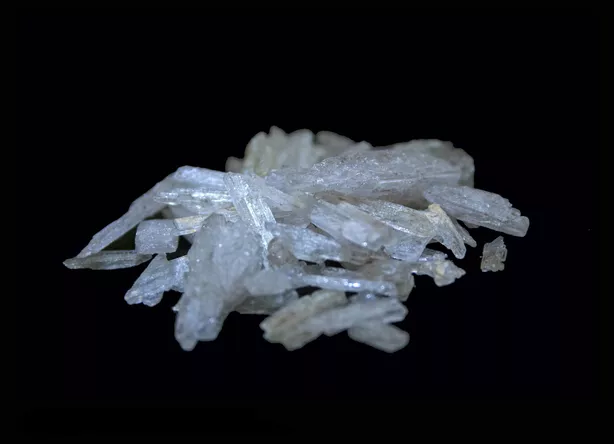

In an analysis released by the Lowy Institute on Thursday, I argue that drug production and trafficking is one of the most serious security issues facing the Pacific Islands region. Methamphetamine, heroin and cocaine trafficking is on the rise. The Pacific Islands are strategically located along both licit and illicit trading maritime highways. The wealth of the Pacific – outlined in a 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent – is also a source of potential vulnerability.

The region’s vast and porous maritime borders, weak jurisdictions and limited enforcement capabilities are key structural challenges and enablers to transnational crime in the region. Consequently, the Pacific Islands have become a production site and trafficking destination as well as trafficking thoroughfare, and indigenous/local crime syndicates now work in partnership with transnational crime syndicates. Furthermore, the criminal deportee policies of Australia, the United States and New Zealand are contributing to the problem, as is the Covid-19 pandemic, by exacerbating the vulnerabilities on which transnational organisations and local crime actors capitalise.

In response to this threat, partners, particularly Australia and New Zealand, have stepped up initiatives to counter transnational crime over the past three years. Working closely with Pacific governments and societies, the international collaboration has led to a number of significant drug hauls in the region and a growing awareness of the complexities associated with countering transnational crime in the Pacific. The Pacific and its partners have responded by strengthening regional policing architecture and governance through enhanced law enforcement mechanisms, but challenges remain as the illicit drug trade adapts and takes root in the region. To combat transnational crime in the Pacific, I recommend the following actions.

First, efforts to combat transnational crime in the Pacific must be guided by the Boe Declaration on Regional Security Action Plan to ensure that intra-regional activities avoid duplication or subversion, and that gaps are identified. The Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat should be provided with the necessary funding to conduct regional and national drug surveys and ensure there is comprehensive data for regional policymakers.

Second, a Pacific-led, partner-supported model to combat transnational crime should be developed to ensure the foregrounding of Pacific knowledge and context-specific expertise as well as opportunities for Australia and New Zealand to further strengthen their relationships. This would by necessity include the provision of more robust cultural training to Australian and New Zealand agencies in order to better enable their officials to effectively bridge the cultural gap with their Pacific Islands counterparts.

Transnational crime in the Pacific, notably illicit drug trafficking and production, is a protracted problem, but not one that is of the Pacific’s own making.

Third, there must be development of policies and strategies that focus on targeting the threat posed by transnational crime and illicit drug trafficking and production to the Pacific Islands region. The Pacific is not a buffer for Australia and New Zealand.

Fourth, drug harm strategies need to be prioritised and funded across Pacific countries. This is an opportunity for Australian and New Zealand NGOs to support localisation through the funding and training of Pacific first responders. This would ensure that drug harm strategies be contextually and culturally appropriate and grounded in a human security approach that draws from law enforcement, government, civil society and traditional power structures as well as prioritises youth across the Pacific as the frontline against drug addiction.

And finally, transnational crime and drug control strategies must be informed by a deeper understanding of how criminal organisations conspire to buy the complicity of key officials, particularly law enforcement, customs and criminal justice agents. The nexus between crime and corruption is often even more opaque than the drug world itself, and is a core driver of insecurity.

Transnational crime in the Pacific, notably illicit drug trafficking and production, is a protracted problem, but not one that is of the Pacific’s own making – rather the region is a casualty of the criminal greed of organised crime and the drug appetite of Australia and New Zealand. The onus therefore lies with Australia and New Zealand to partner with the Pacific in the development of innovative strategies and Pacific-led, partner-supported responses. The landscape is only likely to become increasingly challenging with the emerging intersection between transnational crime and grey-zone activities.

SOURCE: THE INTERPRETER/PACNEWS