By Aubrey Belford (OCCRP), Dan McGarry (OCCRP), Ofani Eremae (In-Depth Solomons), Charley Piringi (In-Depth Solomons), Gina Maka’a (In-Depth Solomons), and Ronald Toito’ona (In-Depth Solomons)

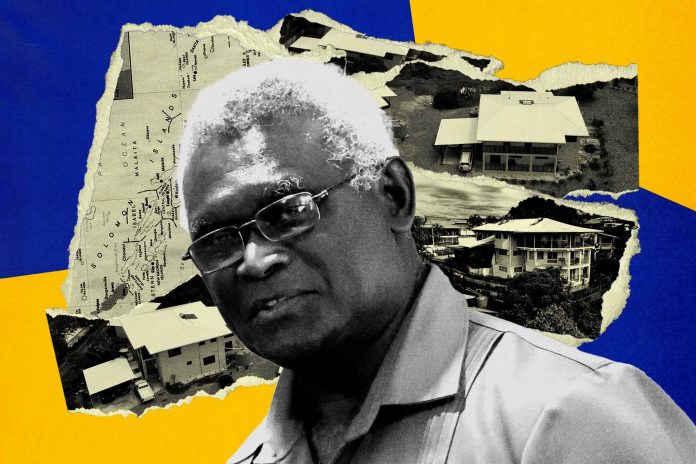

Manasseh Sogavare, the four-time prime minister of Solomon Islands, speaks proudly of his humble origins as a school dropout who once earned a living cleaning toilets and making tea for British colonial officials.

The 69-year-old premier is modestly paid by the standard of world leaders, even after he received a 39-percent pay bump this month that raised his annual salary to SBD$428,560 Solomon Islands dollars, or SBD (around US$50,000).

That relatively low paycheck, however, hasn’t stopped Sogavare and his wife, Emmy, from securing large loans and massively increasing their real estate wealth over the past several years, an investigation by OCCRP and In-Depth Solomons has found.

The couple have built at least eight new houses on land they already owned in and around the capital, Honiara, reporters found. The construction costs are estimated to run as high as several million U.S dollars.

One of the houses, a large, multi-story home in the hillside suburb of Tasahe, serves as the couple’s current residence. Other holdings include what are, by local standards, high-end rental properties in the neighborhoods of Lungga and Henderson, located near the Honiara airport.

Altogether, the houses are believed to have cost the Sogavares between SBD$14 million and SBD$26 million (US$1.7 million and US$3.2 million) to build, according to local property appraisers who reviewed land and mortgage records, satellite images, and drone photos provided by reporters. The estimates do not include additional costs, such as interior furnishings or landscaping.

The value of the properties appears out of proportion with Sogavare’s known earnings. The size and scale of the houses themselves also stand in stark contrast to the living conditions of most Honiara residents, who pay sky-high prices to live in often ramshackle and overcrowded housing.

With Sogavare seeking to secure a fifth prime ministerial term in key elections on 17 April, anti-corruption experts say his fast-growing real estate portfolio — as well as the large loans he obtained to finance it — deserves closer scrutiny.

“He needs to explain to the people: Where did he get all this money from?” said Ruth Liloqula, who heads the Solomon Islands chapter of Transparency International.

Sogavare did not respond to questions from OCCRP and In-Depth Solomons.

“On a PM’s Salary? Definitely Not”

Located at the end of a secluded road overlooking the Ironbottom Sound, the Sogavares’ Tasahe home is still not widely known to the public.

The house is situated on over 1,200 square meters of state land leased by the prime minister and his wife in 2007 but left empty for about a decade. While it’s not clear precisely when construction began, satellite imagery shows that the land went from being completely vacant in early 2017 to containing a completed structure by May 2019.

While the state-owned land it stands on cost relatively little, property valuers estimate the house itself cost between SBD 6 million and 10 million (US$720,000 and US$1.2 million) to build.

According to neighbors and real estate agents, the home was initially rented out to tenants. Financial records obtained by reporters show that by 2020, the Sogavares were receiving SBD$35,000 (US$4,130) a month in rent.

The couple eventually moved into the home themselves after their existing residence — a plot of land in Lungga containing two houses — was damaged after it was targeted in 2021 by rioters opposed to Sogavare’s government. One house was ransacked in the incident; the other was burned to the ground.

When the Sogavares moved to Tasahe, construction crews descended on the Lungga site, demolishing the remaining structures and rapidly building three large new homes in their place.

The Sogavares have also built homes at their Henderson property, which contained just one small house when they purchased the land in 2015.

Satellite images and drone photos show the plot being developed in stages, with two large houses erected sometime between early 2017 and early 2019. By April 2020, a third house had appeared, and a fourth smaller structure was added sometime in 2023. All four houses appear to be rental properties.

Accustomed to the usually sleepy pace of work in Solomon Islands, neighbors told reporters that they were stunned at the speed with which the new houses were built.

“Those of us living around here were so surprised to see three buildings completed in just less than a year, something a Solomon Islander normally couldn’t do,” said Rose Kairi, who watched the Lungga construction work from her home nearby.

Kairi said she saw trucks driven by what appeared to be Chinese workers drop construction materials at the site. Those carrying out the construction were mostly locals, she said.

Rick Houenipwela, himself a former prime minister who served directly before Sogavare’s most recent term, also lives close to the three new houses in Lungga.

Houenipwela’s own home is a sprawling structure cobbled together from typical local construction materials like gyprock, wood, and concrete blocks. He told reporters his own renovations had taken place at a pace more typical of Solomon Islands: in fits and starts.

The Sogavares, he said, appeared to suffer from neither delays nor a shortage of money.

“The machines actually were just stationed there… Sometimes they would have work at night,” Houenipwela said.

“It was really quick by our standards,” he added. “And the standard definitely is high, good work. The material, of course, is of quality standard.”

While prime minister, Houenipwela drew on official income and benefits similar to Sogavare’s. He told reporters he had struggled to pay for his own home improvements, and did not understand how his successor could afford his own far more ambitious construction projects.

“On a PM’s salary? Definitely not.”

A History of Real Estate Controversies

This is not the first time the Sogavares’ real estate dealings have come into question.

In 2007, during Manasseh Sogavare’s second prime ministerial term, the couple raised eyebrows with the original purchase of the Lungga property.

The sale was made with the help of a SBD 2.5 million (about US$350,000) mortgage from Australia’s ANZ bank — supported by a letter from the Embassy of Taiwan, in which the country’s government guaranteed that it would rent the property. Sogavare was a staunch ally of Taiwan at the time.

The loan and the Lungga purchase drew criticism from lawmakers, who accused him of exploiting his relationship with a foreign government for personal gain.

Sogavare defended himself, saying: “I do not see any law in this country that says once you become a prime minister you are not allowed to go to the bank and get a loan.”

“Taiwan came and said it is going to have a long term tenancy agreement with us,” he added. “Taiwan wanted to rent those two houses. What is wrong with that?”

Members of parliament, including those within his own governing majority, saw it differently. Sogavare was removed in a vote of no confidence later that year, in part due to the uproar over the land deal.

Another controversy swirled with the purchase of the Henderson land in 2015, after Sogavare had returned to serve a third term as prime minister. He and his wife bought the land, which satellite images at the time showed to contain a small dwelling, for SBD$1.5 million (about US$190,000).

Questioned in parliament, Sogavare said he had obtained another loan to purchase the Henderson plot. “I wish I had 1.5 million,” Sogavare said at the time.

Land registry documents typically list all mortgages taken out against a property. However, reporters were unable to find any record there showing that Sogavare took out such a loan for Henderson at the time.

An Expensive Building Boom

While the land-purchase deals drew concerns, it has been the past six years that have seen the most dramatic expansion in the Sogavares’ real estate wealth.

In 2018, Sogavare’s lending relationship with Australia’s ANZ Bank — which had provided the mortgage for the Lungga purchase, as well as other smaller loans — ended for unclear reasons. He moved his business across to the French-owned BRED Bank, which on a single day in 2018 granted the politician and his wife three separate, and much larger mortgages worth SBD$ 7,161,590 (US$916,688).

The loans were secured against the properties the couple had acquired in 2007 and 2015, as well as an older, more modest family home in the neighborhood of Vura.

There was just one problem, according to financial experts: The couple likely would not have been able to afford the loans at the time.

Manasseh Sogavare, despite his political longevity, has never served consecutive posts as prime minister in the rough-and-tumble world of Solomon Island politics. At the time BRED agreed to grant him the loans, he was serving as deputy prime minister, earning an annual government salary of just SBD$169,230 (around US$21,000), as well as a housing allowance of up to SBD 240,000 a year (roughly US$30,000).

Nor did the couple have any other substantial sources of income. Company registry documents show the Sogavares had no declared business interests at the time.

That would have left the couple far short of the roughly SBD$824,000 (about US$104,000) in mortgage repayments they would have owed each year (if calculated according to the central bank’s lending rate at the time, 10.7 percent, and paid out over BRED Solomon’s maximum available term of 25 years.)

Financial experts interviewed by OCCRP and In-Depth Solomons said such a shortfall would normally prompt a bank to turn the Sogavares away.

“Based on Sogavare’s income as deputy PM, it doesn’t look like that he’d be able to service that original loan just on his income alone,” said Matt Fehon, a Sydney-based forensic accountant. “There would have to be other sources.”

By 2019, Manasseh Sogavare had returned to the prime ministerial post for his current fourth term, providing a small boost to his salary. Emmy Sogavare soon launched a cafe business that made a modest income. Financial records show the couple also began renting out their former home in Vura for SBD$11,000 (US$1,340) a month.

But even with those gains, the Sogavares’ earnings would still have been swallowed by mortgage payments.

Fehon said BRED Bank may have given the Sogavares a reduced interest rate or allowed them to defer repayments while they built their rental properties. The Sogavares may have also had a third party guaranteeing their loan, he said.

But such special treatment would be risky, and most international banks would have avoided issuing the loans altogether, Fehon said.

“The fact that the individuals are politically exposed persons, you’d want to do additional due diligence,” he said.

“The bank would need to look at the source of those funds, any additional funds, and make sufficient inquiries to satisfy themselves that they’re not illegal payments,” he said.

Such questions are more urgent given Sogavare’s past admission that he received a loan guarantee from Taiwan. While he was previously a staunch advocate of the self-governing island’s interests, he dramatically reversed course in his latest term by switching Solomon Islands’ diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China and signing a secretive security deal with Beijing.

The move has rattled the West and spurred an uptick in Chinese investment in Solomon Islands. China’s government also makes controversial payments known as “constituency development funds” to both Sogavare and his allies in parliament. The 2021 riots that damaged the couple’s Lungga property was driven in part by public anger over Sogavare’s switch in allegiance from Taiwan to China.

Anti-corruption experts say that both Sogavare and BRED Bank should be transparent about how the loans were secured.

“Based on what you’ve outlined by way of the valuations, and his earning capacity, it appears he’s got a large loan and undertaken an expensive construction project that’s beyond his means,” forensic accountant Fehon said.

BRED Bank declined to comment.

“We are not allowed to comment on confidential information regarding our clients,” bank spokeswoman Leila Salimi said.

Making Up the Difference

While questions remain about the Sogavares’ ability to repay the mortgages, property valuers say the loans would not even have been enough to cover the ambitious construction spree the couple would soon embark on.

If estimates from local land valuers on the cost of construction are correct, the roughly SBD 7 million from BRED would cover only half, or even less, of the total construction costs.

Reporters were unable to find any indication on public land documents showing fresh loans to help cover the construction of the three recently constructed Lungga homes, which according to valuers’ estimates, likely cost a total of SBD$4 million to SBD$8 million (about US$470,000 to US$940,000) to build.

However, part of the cost appears to have been covered by an insurance payout of SBD$ 2 million (around US$235,000), according to three sources with knowledge of the matter.

And even though the Sogavares may have lacked the initial funds to pay for their construction and loans, that would no longer be the case. With the homes complete, they can now bring in a handsome rental income that far outstrips the prime minister’s official salary.

Neighbours and real estate agents told reporters that at least some of the couple’s new homes in Lungga and Henderson are currently being rented out. Reporters were unable to learn how much these tenants are paying, but financial records from the previous rentals of two houses owned by the Sogavares, as well as estimates from local real estate agents, suggest that the couple could be earning well over SBD$100,000 (US$11,800) a month in rent.