Controversial proposals to allow deep-sea mining will be centre-stage at global talks in Jamaica from Monday.

It comes after a two-year ban on the practice expired when countries failed to reach agreement on new rules.

Scientists fear a possible “goldrush” for precious metals beneath the oceans could have devastating consequences for marine life.

But supporters argue that these minerals are needed if the world is to meet the demand for green technologies.

The controversy was triggered in 2021 when the tiny Pacific Island of Nauru made a formal request to the International Seabed Authority (ISA) – the UN body that oversees mining in international waters – for a commercial licence to begin deep sea mining.

This triggered a clause that put the ISA on a two-year countdown to consider the application, despite there being minimal regulations in place.

Countries have been meeting regularly since to try and finalise the rules on environmental monitoring and sharing of royalties, but without success.

They have now gathered in Kingston, Jamaica for three-weeks of negotiations.

It comes as opposition to commercial deep-sea mining to harvest rocks containing valuable metals has been growing.

Nearly 200 countries including Switzerland, Spain and Germany are calling for a pause or moratorium on the practice over environmental concerns. It is now expected that countries could be given the chance to vote on a new ban over the next month.

Despite the UK not calling for a new ban, a government spokesperson told the BBC: “The UK will maintain its precautionary position of not supporting the issuing of any exploitation licences unless and until there is sufficient scientific evidence about the potential impact on deep sea ecosystems.”

Marine scientists have raised concerns that limited research has been carried out in the deep ocean to understand the animals and plants that live there and therefore what the impacts deep sea mining could have on them.

Potential techniques to harvest the minerals from the sea floor could generate significant noise and light pollution, and release plumes of sediment which risk smothering filter-feeding species, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

“We mustn’t let this be a new gold rush where we launch headlong into further devastating our planet without really understanding what we’re doing,” said Catherine Weller, director of global policy at the conservation charity, Fauna & Flora.

Scientists recently announced that more than 5,000 different animals have been found in the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) of the Pacific Ocean – a key area earmarked for future mining efforts.

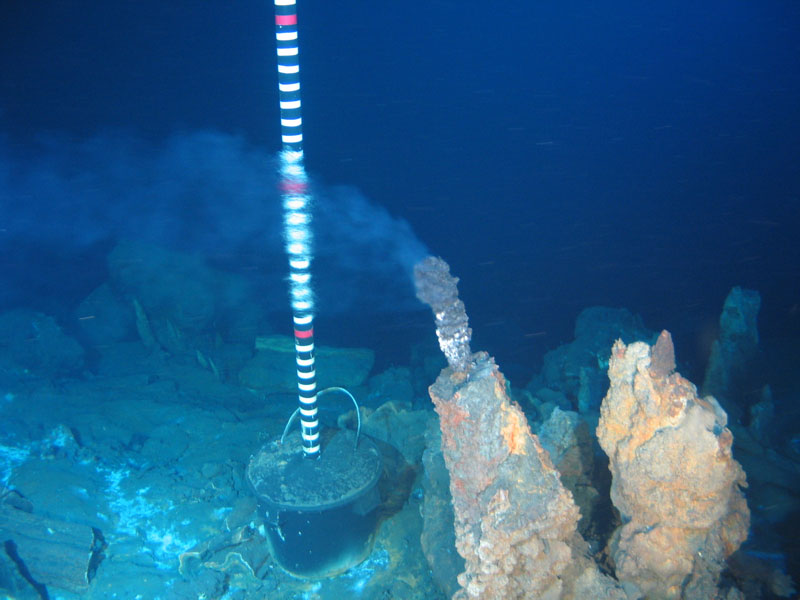

The CCZ and other areas primed for mining like the Pacific Prime Crust are unique environments with hydrothermal vents, underwater mountains, and vast plains up to 6,500m below the surface. Scientists believe they could support uniquely adapted species found nowhere else in the world.

Not all countries are opposed outright to the practice. The ISA has already issued 31 exploration contracts to companies wanting to research the deep ocean, and these have been sponsored by 14 countries including China, Russia, India, the UK, France and Japan.

And the ISA only permits contracts in international waters – countries are free to undertake exploration in their national waters. Last month Norway controversially opened areas in the Greenland Sea, the Norwegian Sea and the Barents Sea covering an area of 280,000 square kilometres (108,000 square miles) for mining companies to apply for licenses.

“We need minerals to succeed with the green transition,” Oil and Energy Minister Terje Aasland said in a statement.

The Metals Company, which is partnered with three Pacific Island nations – Nauru, Kiribati and the Kingdom of Tonga – is determined to press ahead with applications.

The company has said that the deep-sea offers a promising source of metals such as copper, cobalt and nickel needed for technologies such as mobile phones, wind turbines and EV batteries.

Nick Pickens, research director of global mining at Wood Mackenzie, told the BBC many of these minerals are relatively abundant on land but can be difficult to reach.

The Democratic Republic of Congo which holds some of the highest grade of copper in the world is facing inter-ethnic violent conflict in parts of the country.

There are also a limited number of sites for refining the minerals – turning them from their raw form into useful components.

“Deep-sea mining doesn’t necessarily iron out any of these issues…you are still going to have geopolitical challenges,” Pickens said.

SOURCE: BBC NEWS/PACNEWS