Gloria Julia King is the only female member of Vanuatu’s parliament.

Before she was elected last year, there hadn’t been a female MP in Vanuatu for 15 years.

“It was very hard to make the decision to go into parliament because ni-Vanuatu people — in their mind, in their upbringing, in their surroundings — the leadership has always been the men,” she told the ABC’s The Pacific programme.

“If people tell me that I can’t do it, it lights a fire beneath me that makes me want to prove them wrong.”

Despite already being a well-known community leader and businessperson, getting elected was not easy.

“Going into this, I was aware of what I was up against,” King said.

“It’s a man’s world … even being there, I can almost feel that this is not my place”

The Pacific region, not counting Australia, New Zealand, and the French Territories, has some of the lowest levels of women’s political participation in the world.

It’s a problem that has a profound impact on the lives of women, Theresa Meki, a Pacific research fellow at the Australian National University, explained.

“We’ve never had over 30 per cent representation in parliaments all across the region,” she said.

“I think right now we have 52 women members of parliament out of 614 positions of power across the region.

“If we exclude New Zealand and Australia … we do very poorly. Even with them included in the Pacific region, we still do very poorly.”

Parliament should be representative of the population, she said.

“Women are 50 per cent of the population and it’s important for them to be in positions of leadership so that they can have a part in the decisions that affect their livelihoods.”

King said in her society, leadership titles were retained by male family members, citing a Bislama phrase: “The woman’s place is at home.”

“It is a stigma, where everybody just naturally thinks that all politicians should be men,” King said.

No two Pacific countries are the same, Dr Meki emphasises, but there are some common threads in the challenges women face when trying to get into politics.

“The economy, the history of the region, and the culture of elections make it so difficult for them to participate,” she said.

“Traditional positions of power in village or church hierarchies are still dominated by men … and women tend to have less access to the money and resources needed to wage an effective election campaign.”

Lenora Qereqeretabua, the deputy speaker of parliament of Fiji, said women also faced more scrutiny than men in the public eye, particularly online.

“Social media plays a big part in why some women may feel hesitant about standing for any kind of public office,” she said.

“The kind of criticism that we open ourselves to when you’re a woman wanting to take part in politics … [covers everything from] how you wear your hair to what kind of clothes you put on.”

Qereqeretabua first entered parliament in 2018 as a member of the opposition.

“One of the pieces of advice given to me by a seasoned politician, a lady who I respect very much, was grow a thick skin,” she said.

“That doesn’t mean being labelled, being called names is OK.

“It just means you’re going to have to accept that this is something you have to try and change. It may take a long time, but it is doable.”

Quotas and other temporary special measures are often touted as effective solutions but they are also controversial.

“A lot of people don’t think that it’s democratic. But at the stage that we’re in, we need some type of special measure,” Dr Meki said.

Samoa has a quota that dictates at least 10 percent of parliamentary seats must be held by women.

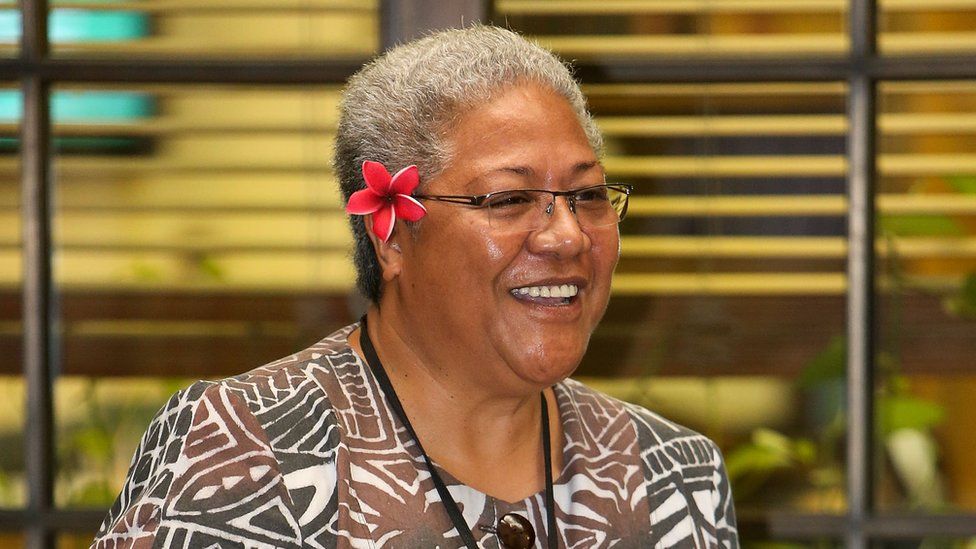

Fiame Naomi Mata’afa became the country’s prime minister in 2021, making Samoa just the second Pacific nation ever to elect a female head of government, following the Marshall Islands with its former president Hilda Heine.

While quotas could be effective at elevating women in politics, Dr Meki said a society-wide approach was needed for lasting change.

“There needs to be more mainstreaming about women as leaders, not just politically … women in aviation, women in mining, different sectors, women as leaders generally.”

King said she led a busy life but hoped her rise to become the first female MP in Vanuatu in 15 years would encourage other women to join politics.

“As a mother of four, I have a full house, I do school runs, I still do school lunches, homework … it’s something that keeps me grounded. That’s my routine,” King said.

“Sometimes I kick myself because I asked myself … I don’t know why or what I’m doing here.

“But it’s a reminder that if women are going to make it here, then maybe I’m going to be the trailblazer.

“If this journey inspires one little girl … enough to make them aspire to be a politician or to go into parliament in the future then … my job is done,” she said.

SOURCE: ABC/PACNEWS