As James Cleverly took the rutted gravel road from the main airport of the Solomon Islands that leads to the prime minister’s residence, he passed under a flag bearing the red background and yellow stars of the People’s Republic of China.

It fluttered prominently on Thursday above the motorcade passing the construction site of a US$50 million (£40 million) stadium for the upcoming Pacific Games – a gift from Beijing and a giant symbol of its growing footprint in the Solomons.

Placards saying “China Aid for Shared Future” lined the corrugated fences around the site.

For decades the Solomon Islands, a visual paradise but impoverished country of some 700,000 people, faced relative diplomatic obscurity to the point where the US closed its embassy in 1993.

But a secretive “security pact” between Beijing and Honiara in 2022 has put it firmly back on the radar.

A string of other deals, including the athletics stadium “state gift”, signalled China tightening its grip around an island chain which is fast becoming ground zero in the great game to control the Pacific.

Fears are growing from Washington to Tokyo of a carefully crafted “elite capture” of the Solomons that could have a potentially huge cost to Western security.

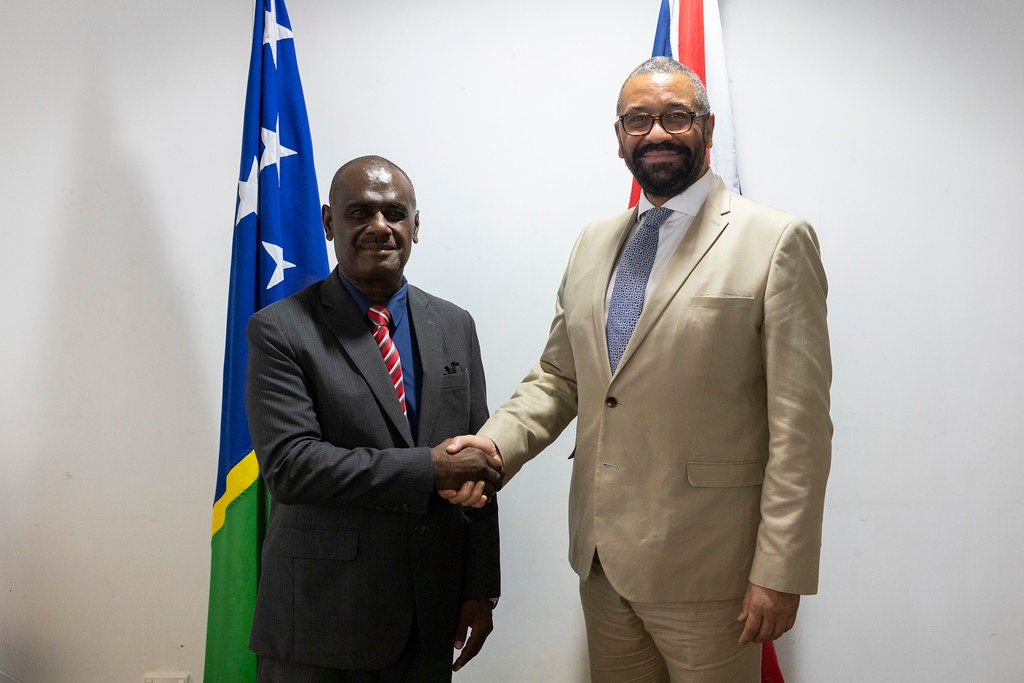

Cleverly, the foreign secretary, arrived in the humid capital of Honiara on Wednesday as part of a push by the West to counter China’s growing footprint across the Asia Pacific, where several other obscure island chains are in a tug of war between Beijing and the West.

In an interview with The Telegraph, he warned that “free” Chinese money comes at a cost, hinting at the well-documented “debt trap” diplomacy China uses to buy up allies.

“No one is going to say no to money and no one is going to say no to free money. But a lot of the conversations I’m having around this region is the recognition that not all free money is free money and that actually whatever relationships they enter into need to be sustainable,” Cleverly said.

Alarm in the West over the Solomon Islands was first triggered by an early leaked draft of the pact in 2022. It referred to Chinese “ship visits” and invoked Beijing’s right to defend its citizens and projects in the Solomons, raising concerns it could pave the way for Chinese troops and naval warships being posted less than 1,200 miles from the Australian coast.

The announcement stunned Canberra. In opposition Penny Wong, who is now foreign minister, called it “the worst Australian foreign policy blunder in the Pacific”. In office, she made the Solomons one of her first ports of call.

Manasseh Sogavare, the Solomons prime minister, has since repeatedly stressed his country’s sovereignty while offering reassurances he will not host a Chinese military base or persistent military presence. Sogavare and China officials were approached for interview.

But the opaque deal and a failed bid by China’s state-linked Sam Enterprise Group to quietly negotiate a 75-year lease on Tulagi, an islet opposite Honiara with a natural deepwater harbour, has left Western and Asian allies nervously guessing Beijing’s intentions. The US embassy has now reopened.

An unprecedented procession of high-level dignitaries are also courting Sogavare.

Among them were the Chinese and Japanese foreign ministers, New Zealand’s deputy prime minister, and Kurt Campbell, the most senior U.S official on the Indo-Pacific.

Cleverly, the first British foreign secretary to visit the Solomon Islands in living memory, was the latest to arrive this week to promise “partnering for the long haul”, in a further sign of the UK’s increasing focus on the security of the volatile region.

Cleverly insisted the UK “can better than match” China’s chequebook “because it’s not just about the money”.

He added: “The expertise that we are sharing with the Solomon Islanders is really key. The fact that we understand them really well because we have been friends and partners for decades, centuries. It’s not just about a bidding war.”

The flashy stadium he passed is one of multiple projects that blur the line between benign diplomatic activity, genuine economic investment opportunities and state power projection.

Diplomats speaking to The Telegraph in the region cautioned against premature over-reaction, but they are closely watching Beijing’s interests and do not dismiss concerns over moves to invest in port facilities based in an archipelago that once hosted the British, Japanese and U.S navies.

“China is trying to expand its chessboard to play a strategic game with the US,” said one senior official.

The previous attempt by a company with ties to China’s defence ministry to buy Tulagi – ultimately blocked by the attorney general – has left little doubt that China is seeking to establish a naval foothold in the southern Pacific.

The overturned agreement had contained references to a possible oil and gas development as part of a “special economic zone”.

Peter Kenilorea, a prominent opposition MP and son of the first Solomon Islands’ prime minister, said he was already hearing from landowners that they had been approached individually by people representing Chinese interests.

“It is still ongoing. They are trying it in a different way,” he said, adding that port developments in Isabel province and at Noro international port may also be on Beijing’s radar.

“I’m seeing it all in the same vein in terms of the importance that we present to an expansionist PRC,” he said.

Across the Iron Bottom Sound strait, back on the main island the Royal Navy’s HMS Spey docked on Saturday, underscoring Britain’s anxiety to maintain alliances and contain China.

The ship’s visit was described as an exercise in relationship building and fact-finding over how the Spey could best assist with environmental and fisheries challenges and future humanitarian aid, Commanding Officer Michael Proudman said.

If the simmering Savo volcano, an alarming 21 miles from Honiara, were to suddenly blow, the Spey’s potential to carry aid supplies and produce five tonnes of fresh water a day could be life-saving.

But Commander Proudman was guarded about the more pressing issue of a future conflict with China in the region as Beijing eyes up Taiwan and more disputed territories in the South China Sea.

“I haven’t got a task to prepare for conflict,” he said, stressing that the ship’s weapons were defensive, not offensive in nature.

But he added: “The key lesson that we have learned from Ukraine is that what happens in one place affects the entire world.”

It was a carefully-worded caution but the historical undertones of the Solomon Islands’ strategic importance are impossible to miss.

Solomon Islanders are still killed today by the vast quantity of unexploded World War 2 bombs left behind after ferocious battles between the Japanese and Allied forces to control access to the Pacific.

Allied victory was pivotal in preventing Japan from cutting Australia and New Zealand off from the United States, opening the way for the recapture of the Philippines and choking Japan’s access to resources in occupied Indonesia.

Western allies are wary of history repeating itself as China grows its military ambitions.

A presence on the strategic outpost could be a game changer in a conflict over Taiwan, putting China within immediate reach of the Australian coast, and crucial to its anti-access/area denial or A2/AD tactic to deny an adversary’s freedom of movement on the battlefield.

In contrast to the UK’s soft power approach, China’s diplomatic reach into the Pacific nation is more complex, often relying on the complicated role of quasi-governmental Chinese companies which can act both as entrepreneurs and agents of the state to promote its geopolitical ambitions.

As China expands its presence, there is growing unease about suspected disinformation campaigns against critics of its intentions.

Beijing now exerts more influence over the training of the police, and a planned US$66 million (£53million) loan from Beijing to build 161 mobile communication towers, supplied by Chinese telecoms giant Huawei, has prompted fears of surveillance and that Honiara could fall into debt.

Like many Chinese deals, including the security pact, the progress of the Huawei project remains shrouded in secrecy.

Malaita, the Solomons’ most populous province, was a renegade holdout on the deal, refusing to take its allocated 27 towers, but that decision may now be in question after the sudden ousting of its premier Daniel Suidani, a fierce opponent of the diplomatic switch from Taiwan.

Suidani was pushed out in February 2023 by a motion of no confidence in the provincial assembly after being accused of misappropriating funds – a charge his supporters say is politically motivated.

In a letter of disqualification from the central government, he was accused of “failing to recognise the One-China policy” and that he had “colluded with Chinese Taipei”, Beijing’s name for Taiwan.

One of the first acts of the new provisional authority was to revise the so-called “Auki Communique” which banned China-funded projects in Malaita. Martin Fini, the new premier, met swiftly with the Chinese ambassador.

His deputy, Joe Hereau, told The Telegraph the new administration “did not have space for discrimination” and was now open to Chinese investment.

MPs frequently now wear Chinese flag pins on their lapels, said Kenilorea, a prominent opposition MP.

“I raised it in parliament last year as part of the decorum that the speaker should perhaps look into,” he said. “There should be only one flag if you want a pin on your coat, and it’s not the flag of China, or of Australia or the US, it’s the Solomon Islands.”

But many Malaitans are upset about the unseating of a popular leader and remain wary of China’s goals and communist regime.

“We believe in our own principles and values,” said Phillip Subu, a local youth activist.

“Our biggest fear is not about the Chinese people but the Chinese Communist Party because they have a totally different system from democracy. We are afraid it might influence our government system.”

The CCP faces resistance more generally from the Solomons’ devout Christian population.

But Kenilorea predicted his country might ultimately be squeezed by economics and the weight of geopolitics.

“We put ourselves in that position by signing that [security] treaty and we inserted ourselves unnecessarily into a geopolitics potential quagmire,” he said.

SOURCE: THE TELEGRAPH/PACNEWS