The best approach to safeguarding democracy in the region is for both countries to demonstrate the prosperity and human flourishing that can flow from good governance.

By Grant Wyeth

Are Australia and New Zealand overlooking democratic decay throughout the Pacific Islands for fear of pushing their neighbors closer to China? This is the assertion of the leader of Fiji’s National Federation Party, Biman Prasad. Writing for the Australian National University’s Development Policy Centre, Prasad claims that at the recent Pacific Islands Forum leaders’ meeting in Fiji, there was a “deafening silence on declining standards of democracy, governance, human rights, media freedom and freedom of speech issues” in the region.

China’s burgeoning activity and influence in the Pacific have proved confronting to both Canberra and Wellington. In response, both countries have launched initiatives to seek to reaffirm their positions as the Pacific’s major influences: Australia’s “Pacific Step-Up” and New Zealand’s “Pacific Reset.” These initiatives have sought not only to increase spending in the region but to do so in a manner that reframes the relationship away from one between an active donor and a passive recipient. The objective has been to create partnerships that demonstrate a familial bond with the region.

Yet frank, honest discussion should be considered essential for any family. To avoid this is to undermine a family’s most fundamental building block. Australia and New Zealand would be well aware that there are democratic difficulties within the Pacific. However, raising concerns in a superior manner may come across as too paternalistic, treating Pacific Island countries as sons and daughters, rather than brothers and sisters. Respect among equals has to be at the center of Canberra and Wellington’s Pacific engagement.

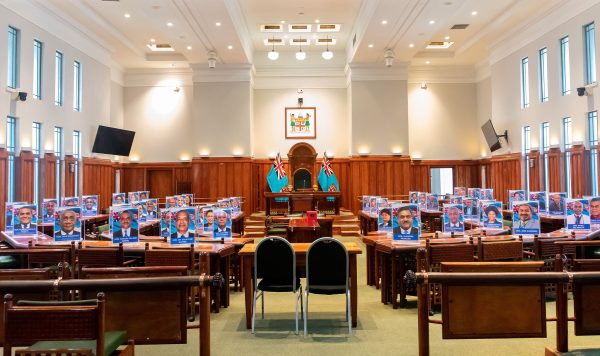

Prasad is chiefly concerned with his own country. Fiji has been and continues to be a country where it is a struggle to maintain liberal-democratic norms. Fiji’s numerous coups are an obvious indication of democratic failure. Despite the new Fijian constitution’s laudable aims to move the country’s governing institutions away from being race-based – which was one of the main drivers of the country’s coup culture – according to Freedom House, the governing FijiFirst party “frequently interferes with opposition activities, the judiciary is subject to political influence, and military and police brutality is a significant problem.”

Beyond Fiji, the problem of political violence at each Papua New Guinea election is serious, and an issue that all regional states have an interest in finding solutions for. However, democracy’s struggles in PNG might be less a failure of governance and more a problem of trying to shoehorn Western institutions onto a society of immense complexity, with traditional social structures and obligations that are often in tension with these institutions. Democratic “lessons” from outside powers may be a futile pursuit.

Yet it is PNG’s neighbor in the Solomon Islands where Canberra and Wellington may be treading lightly due to a fear of creating – or consolidating – a counterforce toward China. Since switching its diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China in 2019, the government of Manasseh Sogavare has developed a more intimate relationship with Beijing, including a security agreement that has deeply unsettled Australia and New Zealand. Sogavare has bristled at scrutiny of the agreement, which may be less about Solomon Islands’ security and more about maintaining Sogavare’s own political power.

However, there are signs that Canberra is interested in promoting liberal-democratic norms in the Pacific but is doing so in a more subtle manner, as heavy-handed methods could be counterproductive. On a recent visit to the Solomon Islands, Australia’s Foreign Minister Penny Wong spent considerable time answering questions from local journalists. Although this was partially a way of contrasting herself with her Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, who refused to answer journalists’ questions on his recent trip to the Pacific, it was also a demonstration of a norm within Australian politics that politicians make themselves available for public scrutiny.

Australia and New Zealand do need to be able to have open and honest discussions with their neighbors. However, the best approach to safeguarding democracy in the region is for both countries to demonstrate the prosperity and human flourishing that can flow from good governance. And for Australia especially, taking the Pacific’s primary concern in climate change seriously would also be an enormous soft power boost that could have major flow-on effects to Pacific democracy.

Of course, there is a distinct irony that in order to counter the dehumanising effects of authoritarian regimes, states like Australia and New Zealand need to be less vocal on liberal-democratic ideals. However, there is also some merit to embracing subtlety in promoting these ideals. No one likes being scolded or hectored for their own behavior; this itself can feel dehumanising and can often lead to an entrenchment of negative behavior. Canberra and Wellington’s re-engagement policies in the Pacific will be as much about tone as material contributions.

SOURCE: THE DIPLOMAT/PACNEWS