By Rosie Julin

United Nations member states have tried for years to reach a global agreement that would protect marine life on the high seas—those parts of the world’s oceans that fall beyond the jurisdiction of any individual country.

The endeavor is seen as hugely important for protecting the world’s biodiversity and limiting the impact of climate change. While existing laws and treaties address marine and maritime activities within countries’ jurisdiction, very little extends to the high seas, which include about 95 percent of the world’s oceans in terms of volume.

Member states began discussing the issue in 2004, with delegates meeting every two years. By 2020, the parties appeared to be close to striking a deal, but the outbreak of COVID-19 that year put the talks on ice.

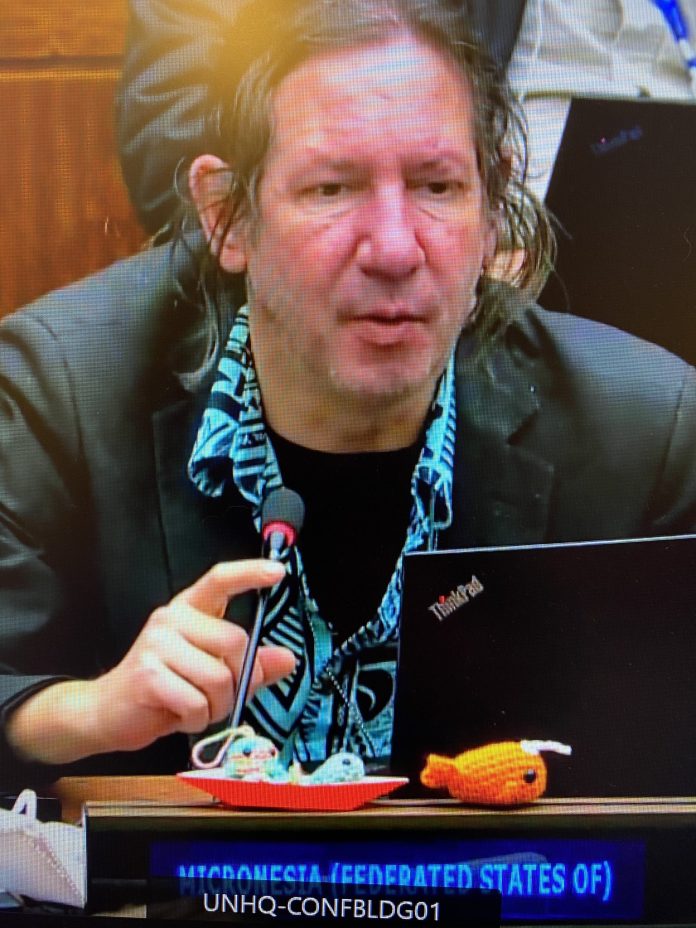

The negotiating process finally resumed this week in New York, where delegates gathered for two weeks of talks. Member states remain divided on several key issues, but some experts believe an agreement is likely this year.

Here’s what you need to know about the prospective treaty, which member states have shorthanded as BBNJ—or Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction.

What’s in it?

The treaty would regulate marine activity on the high seas, curbing overfishing, mining, polluting, and other actions that threaten biodiversity and accelerate climate change.

It includes four sections that address issues around benefits of sharing marine genetic resources, environmental impact assessments, climate change and ocean resilience, and the expansion of marine protected areas.

How would a high seas treaty protect marine life?

Marine protected areas currently span just over seven percent of oceans and an even smaller proportion of the high seas. Environmentalists want the protected areas extended to 30 percent of world oceans by 2030.

“The high seas … need to be part of that solution,” said Lisa Speer, a marine scientist and the director of the International Oceans Programme at the Natural Resources Defence Council.

The restrictions in these protected areas are designed to prevent overfishing and range from moderate limits to “no-take” policies—sometimes drawing criticism from fishing interests.

But Duncan Currie, an environmental lawyer who often serves as an observer at international meetings on marine issues, said the restrictions can actually benefit the fishing industry.

“It’s not just closing down the fishing grounds, it’s actually positively contributing to the productivity of fishing grounds,” he said.

What’s the connection to climate change?

The U.S government estimates that 90 percent of the world’s warming has taken place in the oceans. The phenomenon is exacerbated by other factors in the water, including overfishing and destructive fishing practices, seabed mining, and plastic and chemical pollution.

Speer, the marine scientist, said a high seas treaty would reduce the additional stressors and amounts to “the best way to give the ocean a fighting chance in the face of climate change.”

It would also benefit communities that live in coastal areas—roughly 40 percent of the world’s population—and subsist on fishing.

Will it be adopted?

The negotiating process has gone on for years, but some analysts sense a new urgency among member states. Last month, nearly 50 countries formed a “high-ambition coalition” aimed at getting the deal done quickly.

Other countries, including Russia and Iceland, have taken a more conservative approach, calling for fisheries to be excluded from the agreement. Fishing accounts for a significant portion of Iceland’s GDP, making this small country one of the world’s top fishing nations. And China, which produces a third of the world’s fish, is a key player in the high seas.

The United States has largely favored maintaining the status quo as well, and any agreement would require Senate ratification, which could be a challenge given the polarization in U.S politics.

But advocates say the United States would likely engage with an agreement even absent ratification.

“Our hope [is] that under the Biden administration, the U. S will take a much more progressive role in advancing both dramatically strengthened assessment and management of human activity,” Speer said.

SOURCE: FOREIGN POLICY