A giant patch of garbage in the Pacific Ocean is now “an immense floating plastic habitat” for marine animals clinging to its plastic debris, researchers have found

Coastal plant and animal species that have been carried out to sea on plastic debris aren’t just surviving on an area of the ocean called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. They’re building communities and thriving, according to research published recently in Nature Communications.

Researchers discovered coastal creatures including anemones, shrimplike amphipods, barnacles, crabs and seaweed found a way to survive in a place previously considered inhospitable: rafts of rubbish floating between the coast of California and Hawaii, lead author Linsey Haram said.

“It’s creating opportunities for coastal species’ biogeography to greatly expand beyond what we previously thought was possible,” Haram said.

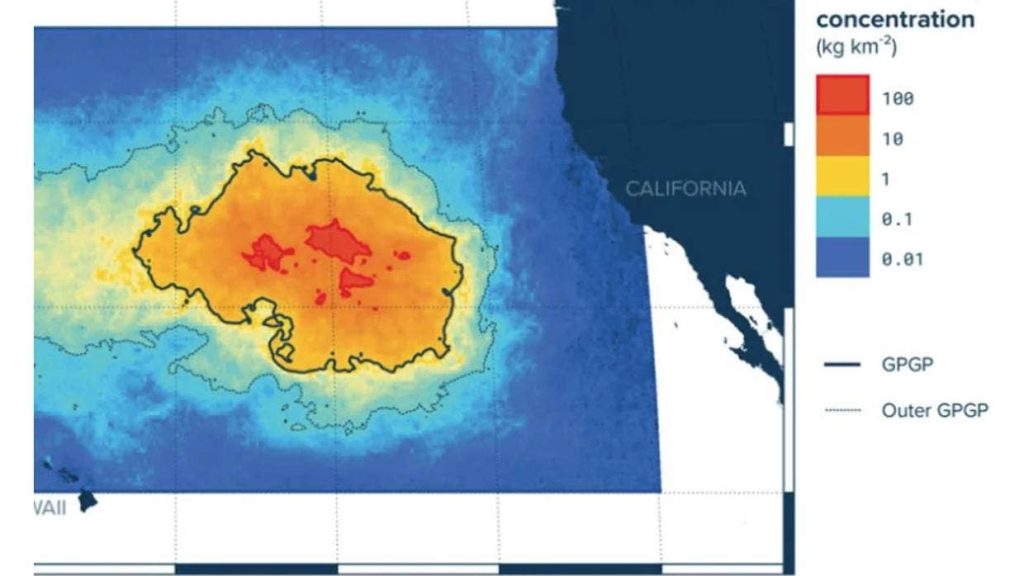

While there are at least five garbage patches in the world, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, also called the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, holds the most plastic. This patch, about twice the size of Texas, contains at least 79,000 metric tons of it, including fishing nets, bottles and tiny plastic fragments called microplastics, according to a 2018 study published in Nature.

But the “garbage patch” is a misnomer, said Luca Centurioni, a co-author of the research published last week. He said much of the plastic is microplastics often too small to see. As ocean currents swirl in a vortex, these microplastics and larger pieces of pollution are pulled into the patch.

“A lot of people tend to think it’s a floating island,” he said. “It’s actually pretty dispersed, but the concentration of plastic debris is higher than in other places. So you may be able to find large pieces but a lot of it is also microplastic.”

The team’s research began in 2018 in this patch of garbage, where they collected trash to study. Because ocean expeditions are expensive, Haram said the team relied on non-profits and citizen science groups to help collect debris before photographing and preserving it. Back on land, researchers identified the species found on the trash.

Haram said she couldn’t say exactly how many species they found because that information will be released in upcoming studies. But she said the team discovered a diverse spread, including coastal and open ocean species that had joined together to form a new, mixed community.

And the species were reproducing in their new plastic homes with some producing larvae and eggs, she said.

Their findings build on previous research, especially from the environmental non-profit group the Ocean Cleanup, detailing the extent of plastic pollution in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, as well as past studies on the invertebrates associated with floating plastic in the area, Haram said.

After the 2011 Japanese tsunami, scientists recorded nearly 300 coastal species crossing the ocean on rafts of debris and arriving on the shores of Hawaii and the US West Coast, according to a 2017 study.

But sightings of coastal species directly on plastics in the ocean have been rare, according to last week’s study.

While scientists knew coastal species could hitchhike out to sea on debris, these rafts were seen as infrequent and temporary because they’d quickly disintegrate. But as plastic pollution has increased, researchers wrote that these “plastic rafts create a more permanent opportunity for coastal species … to colonise in the open ocean.”

“Coastal species inhabiting the open ocean exceed previous expectations,” Haram said. “We knew that coastal species could survive temporary rafting events, but coastal species inhabiting open ocean ecosystems for prolonged periods of time may require us to rethink the biogeography of coastal marine species.”

But when asked how these species survive in the harsh conditions of an open ocean with little food and shelter, Haram said, “We don’t know.

“The floating plastic provides the structure needed for survival but beyond that, we don’t know what they are eating, what’s eating them, how long they’re living, or how quickly they’re reproducing,” she said. “These are questions that need to be answered.”

Among the “sea of questions” that remain unanswered, Haram said scientists are unsure about the extent of coastal species inhabiting the open ocean on plastics and how coastal and open ocean species are interacting. Researchers are also concerned the debris may help transport invasive species that could disrupt local ecosystems.

As the effects of plastic pollution grow, these questions are becoming more pressing, Centurioni said.

The amount of plastic pollution in the ocean could triple by 2040, according to a 2020 report. If no action is taken to curb plastic pollution, the amount of plastic flowing into the ocean will rise from 11 million tons to 29 million tons in that time, leaving a cumulative 600 million tons in the sea.

The U.S is the worst offender as the world’s leading contributor to plastic waste, according to a November report that says the country generated about 42 million tons of plastic waste in 2016 – almost twice as much as China.

“With the way we are modifying the environment, there are consequences we can’t even imagine,” he said. “People should really start to realise that at the scale at which we’re introducing pollution, the consequences of that can heavily impact the environment in a way we’re unable to think of right now.”

SOURCE: STUFF NZ