One of the world’s most important courts will advise states on their responsibilities for curbing global emissions and the legal consequences of inaction, following unprecedented consensus on the subject at the UN.

At a General Assembly meeting in New York Wednesday, governments approved a resolution recognising the huge challenge of climate change and calling on the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to provide an advisory opinion on how it intersects with international law.

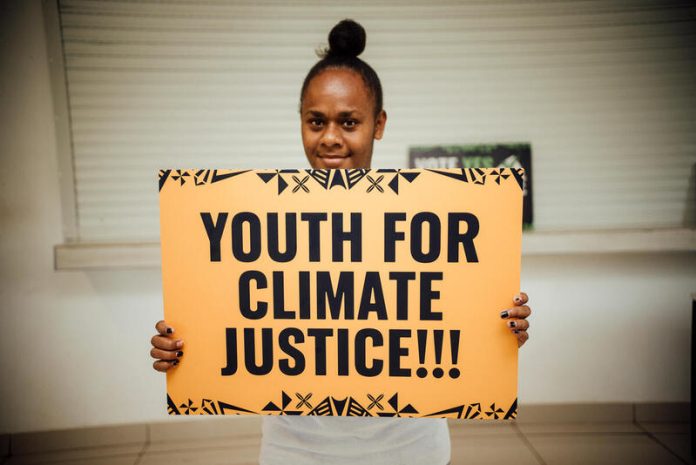

Ishmael Kalsakau, prime minister of Vanuatu, which led the initiative alongside a group of young people, called the decision “a win for climate justice of epic proportions”.

The Pacific island nation is currently in a national state of emergency after two tropical cyclones devastated the island in the space of just a week.

An advisory opinion from the ICJ interprets existing international law rather than creating new legal obligations, and it is not legally binding. But it is highly influential.

Nilufer Oral, a member of the UN International Law Commission and director of the National University of Singapore’s Centre for International Law, said the opinion would “provide clarity and guidance on the legal obligations of states when it comes to climate change, and the legal consequences of failing to act”.

Among other things, it will consider states’ human rights responsibilities and their intergenerational duties.

The resolution marks “a turning point in the pursuit of climate justice,” said Caio Borges, law and climate coordinator at Brazil’’s Institute for Climate and Society.

“The court’s opinion will undoubtedly shape the trajectory of future international climate negotiations and climate litigation at both domestic and international levels,” Borges added.

Vanuatu’s climate change minister Ralph Regenvanu said there had been “overwhelming global support” for the resolution, which was co-sponsored by the vast majority of UN states. But it took four years to get to this point.

Cynthia Houniuhi was in her final year of law school at the University of the South Pacific in Fiji campus, doing a course on international environmental law, when her classmates began discussing ways of promoting climate justice. One of the ideas on their list was seeking an advisory opinion from the ICJ.

“To be honest, at first I was very hesitant when this idea was being discussed,” said Houniuhi. “I mean, let’s be real here; it was too ambitious. How can a small group of students from the Pacific region convince the majority of the UN members to support this initiative?”

What moved her, in the end, was seeing communities already doing their best to adapt to climate impacts, and watching the advocacy efforts of civil society and her government.

“What is the use of learning all this knowledge if it’s not for our people to fight the single greatest threat to their security?” she asked herself. “This was an opportunity to do something bigger than ourselves, bigger than our fears.”

Houniuhi was one of 27 students to form Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change, who petitioned their teachers and lecturers about the idea, and crowdfunded 80 Fijian dollars to pay for a banner.

With growing support, they approached the Vanuatu government, which welcomed the idea and galvanised a core group of 18 countries. Houniuhi, who is now studying for a masters in environmental law at Sydney University, said the support shown her group has been “overwhelming”.

Getting the explicit support of so many nations was the result of a huge diplomatic effort around the world, said Ambassador Odo Tevi, Vanuatu’s permanent representative to the UN.

The resulting opinion will undoubtedly be used as a key piece of evidence in the growing number of climate lawsuits against domestic governments. Earlier today, for example, the European Court of Human Rights heard its first two climate cases against Switzerland and France.

But those behind the initiative made a concerted effort to avoid laying blame on states. Oral said the aim should not be to sue states, noting that previous advisory opinions from the ICJ have not sparked a swathe of legal actions.

Experts say it could encourage reviews of national climate plans, and push states to look hard at their domestic targets, aiming for stronger policies to cut emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

“It’s really being able to give… that extra legal incentive for states to understand that they have to take action now. We know from the most recent IPCC report, they have very little time,” said Oral.

Vanuatu took a long look at its own international obligations and last year submitted a more ambitious NDC, which included over 140 commitments on mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage. “This is exactly the kind of outcome we hoped for from the ICJ’s advisory opinion,” said Regenvanu.

Regenvanu said states might also use the opinion to negotiate a complementary legal instrument like a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty; an international campaign for such a treaty is rapidly building with the forthright support of Pacific island nations. Or it could add fuel to efforts to add the crime of ecocide to the International Criminal Court’s Rome Statute.

The ICJ has not been specifically asked to provide an opinion on the highly politicised issue of loss and damage, although the resolution emphasises the urgency of “averting, minimising and addressing loss and damage associated with those effects in developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to these effects”.

But Regenvanu said it would complement efforts to roll-out loss and damage finance and might affect rules around it are interpreted.

Speaking at the Economist Impact’s sustainability week, UN Secretary-General, António Guterres said the opinion would help the UN and member states take “the bolder and stronger climate action that our world so desperately needs”.

The court will organise hearings over the next few months, and an advisory opinion will be issued between six and 12 months later.

Pacific island students and other young people are writing a handbook explaining how young people and civil society organisations can contribute to the process, which will be published soon.

SOURCE: CLIMATE HOME/PACNEWS