by Tarcisius Kabutaulaka

The tumultuous dispute over the selection of the Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), which led to Micronesian countries deciding to withdraw from the premier regional organisation, provides an opportunity to re-examine the idea and vision of Pacific regionalism and the concept of the “Pacific Way”.

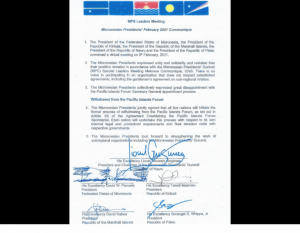

The Micronesian countries argue that according to an unwritten convention, it was their sub-region’s turn to fill the Secretary General (SG) position. Palau President Surangel Whipps Jr. said:

“If we want to bring the Pacific together… let’s treat everyone equally – that’s why it’s so important that the SG be selected on a rotational basis [between Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia].” The last time a Micronesian held the top regional position was 20 years ago.

By March 2021, the three US-affiliated states – Palau, Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) and Marshall Islands – had started the divorce proceedings. FSM President David Panuelo has said “the train has already left”, casting doubt on any hopes the Micronesian countries will reverse their decision. Nauru and Kiribati have not yet started the process.

Robert Underwood, Guam’s former delegate to the US Congress, referred to this as a “Micronesian revolt” and “Micrexit”. He said Micronesian leaders “are justifiably unhappy” and that this “could have been avoided if Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas and American Samoa were members of the Forum” just like the French territories of New Caledonia and French Polynesia.

Micronesian scholars, Katerina Teaiwa, Vincent M. Diaz and Julian Aguon highlighted the Micronesian countries’ shared historical experiences, cultural connections, diversities and leadership on issues of ocean policy, anti-nuclear weapons and climate change. They say the PIF decision was a “strong showing of Micronesian unity that should not be underestimated.”

The Micronesian countries’ sense of hurt and their united and assertive response should not be underestimated. Nor should we underestimate the disruptive impacts of this quarrel on the future of Pacific regionalism.

It could potentially weaken the power of island countries’ collective diplomacy, vital to achieving the South Pacific Nuclear-Free Zone Treaty, the US-South Pacific Tuna Treaty, the Biketawa Declaration and more recently in Pacific Islands leadership on climate change issues. The Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA) is an example of collective diplomacy around a particular resource.

The dispute gives Pacific Islanders the opportunity to have frank and deep conversations about the ideas and values that inform Pacific regionalism, examine how we perceive and treat each other, and appraise the relevance and effectiveness of regional institutions, including Council of Regional Organisations in the Pacific (CROP) agencies and non-state organisations.

A central idea in this discussion is the “Pacific Way”, which is often touted as foundational to Pacific diplomacy. FSM’s President Panuelo said the dispute “has planted the seeds of mistrust

and a noticeable ‘erosion’ of honouring the Pacific Way.”

But what exactly is the Pacific Way? Is there a single Pacific Way or multiple ways? Does it manifest itself in the same way across the region and over time? Who determines what the Pacific

Way is? Does the Pacific Way embody both a collective regional identity as well as valuing the sub-regions? How does it offer a resolution to the current dispute? These are questions worth reflecting on.

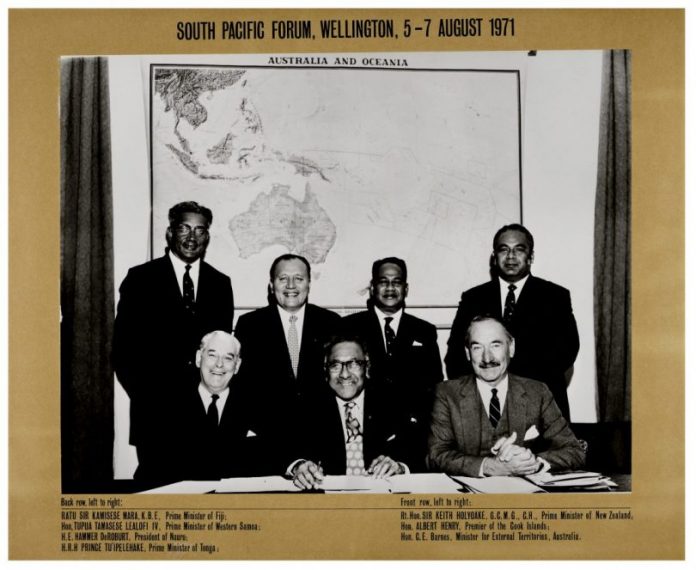

When Fiji’s first Prime Minister, Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, invoked the term at the UN General Assembly in 1970, he was referring specifically to Fiji’s peaceful transition to independence. Over the years the term has been used to mean doing things in ways that are mutually respectful, inclusive, consultative, consensual, flexible and allow for compromise. The Pacific Way is a set of ideas, visions and processes that are dynamic, reinventing itself under new contexts while simultaneously grounded to core values.

Over the years these values have been marginalised in favour of the increasing bureaucratisation of regionalism and regional organisations. The Pacific Way has become subsumed by bureaucratic requirements and processes. While such requirements are important, they need to be grounded in regional values.

Disagreements amongst PIF member countries is not new. Greg Fry highlights past disputes, often around perceptions of Polynesian dominance. Fry recounts his 1975 interview with Melanesian leaders who “felt that the Polynesian leaders looked down on them, making them feel like second-class citizens in the Pacific regional community.” In these instances, leaders reached across this divide to create strong relationships, which saw the great collective diplomacy gains of the 1980s.

The current falling-out also illustrates how Pacific Islanders have appropriated the colonial divisions of Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia. Transform Aqorau, the former CEO of the PNA, states “there are already sub-regional groupings. The region is multidimensional, and constantly changing, and to assume that it should always be united, perhaps underestimates the emergence of strong national and sub-regional impulses.”

Despite these divisions, relationships continue to exist and are strengthened across these arbitrary and racialised boundaries. The current quarrel gives Pasifika peoples the opportunity to have deep conversations about our collective regional identity, and our belongingness to and shared responsibilities to this blue continent. At the same time we must bear in mind the dynamism, multilayered nature and complexity of Oceania, its people and the issues that concern us.

How metropolitan powers respond to and take advantage of the situation is also important. The PIF provides a one-stop-shop for diplomatic courtship between its 18 member countries and territories and the 18 dialogue partners at a single venue. It will not be the same without the five Micronesian countries.

Perhaps there are many in Washington DC, Canberra, Wellington and other metropolitan countries jostling to save Pacific regionalism. It would be best for them to support, but not interfere or attempt to take advantage of the situation. There are ongoing conversations amongst Pacific Islanders aimed at creating better understandings going forward.

This dispute, while disruptive, provides us the opportunity to re-examine the Pacific Way and chart new routes and new forms of Pacific regional partnerships.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.

Tarcisius Kabutaulaka is Associate Professor and Director of the Center for Pacific Islands Studies at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. He is the author of “Mapping the Blue Pacific in a changing regional order”, in The China alternative: changing regional order in the Pacific Islands, edited by Graeme Smith and Terence Wesley-Smith, ANU Press, 2021.