A U.S-based ecologist says deep-sea mining is edging closer to commercial reality as extraction technologies advance and demand for critical minerals rises, but scientific uncertainty and unfinished global regulations continue to shape a complex debate for Pacific Island governments and the international community.

Dr Carrie Pucko, who teaches biology at the University of Georgia and studies international policy, defines deep-sea mining as “any mining, any extraction that takes place below 200 meters below the surface of the ocean,” with current commercial focus on polymetallic nodules, a rock-like mineral deposit scattered across the seabed.

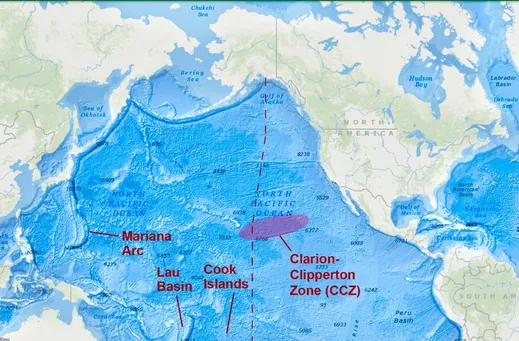

One of the main proposed starting points for large-scale nodule collection is the Clarion–Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a vast Pacific region considered to hold some of the world’s densest concentrations.

“It is an area as large as Europe,” Dr Pucko said, describing the CCZ as lying in international waters between Hawaii, Kiribati and Mexico. Because it falls outside national Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ), she said the governance framework is complex.

“These aren’t waters that are traditionally part of the EEZ of any country, which makes the regulatory environment… very complicated.”

“Picking up nodules,” not blasting rock

Dr Pucko said deep-sea mining differs significantly from common images of land-based mining.

“Instead… what we’re doing as part of deep sea mining is really just picking up nodules off the bottom of the ocean,” she said.

Most proposals rely on subsea collector vehicles, “little autonomous vehicles”, operating at depths of “4,000 to 6,000 meters” to gather nodules and pump them to a surface vessel through riser pipes.

One widely discussed model involves tracked “crawler” collectors that use “high-powered water jets” to lift nodules before suctioning them upward. However, she cautioned that most environmental data comes from exploratory-scale machines.

“The commercial scale operation is likely to use crawlers that are two to three times larger than this,” she said, warning that scaling up could alter sediment plume behaviour and other impacts.

The process generates sediment plumes both at the seabed and when nodules are washed on surface vessels. The mixture of seawater and fine mud is discharged back into the ocean.

“This is one of the places where there’s the potential for some impact on mid-water ecosystems,” she said.

A “lighter-touch” concept guided by AI

Dr Pucko also highlighted an alternative design proposed by Impossible Metals, involving neutrally buoyant collectors that “glide across the bottom without touching the sediment,” using mechanical arms to retrieve nodules individually.

“They’re also saying that those little arms can pick up individual nodules that aren’t occupied by organisms,” she said.

When PACNEWS asked how machines would distinguish life-bearing nodules, she explained the system relies on image recognition: “This is using AI technology to image each nodule… to identify organisms that are attached.” However, she stressed that large-scale performance remains unproven.

“The level to which this technology works is still pretty up in the air,” she said. “There are a tremendous number of species down here that haven’t been identified, even big ones.”

Why now: minerals and market uncertainty

Interest in deep-sea mining is closely tied to demand for minerals used in clean energy systems. “As we think about moving towards a more electrified grid… it’s going to rely a lot more on batteries… that all require critical minerals,” she said, noting that some land-based reserves “are probably going to run out within the next 20 to 30 years” for certain minerals.

She said nodules contain manganese, nickel, cobalt and copper – metals aligned with many current battery designs.

“These things overlap really like incredibly well,” she said, describing nodules as “all of these things in one little package.”

Estimates suggest “21.1 billion tons” of nodules may be present in the CCZ.

But she also warned that battery technologies are evolving. The emergence of sodium-ion batteries, particularly in China, could reduce demand for some nodule metals.

“A change in that market of those metals is going to mean a change in the market for these nodules,” she said. “So it may not be an economically viable venture forever.”

Environmental concerns: slow recovery, permanent change

Dr Pucko said environmental concerns include direct seabed disturbance, sediment plumes, and broader ecosystem effects.

She described the CCZ seabed as “really flat,” “very old,” cold and dark, with relatively low visible animal density, “only about one and a half individuals per square meter”, but high biodiversity.

Surveys suggest “between 6,000 and 8,000 species” may occur there, yet “only about 5,000… have been actually described.”

“Lots of organisms use those nodules to live on,” she said. Removing nodules, therefore, removes habitat.

“And when we take away those nodules, they’re not coming back,” she said, noting growth rates of “a couple of millimetres every million years.” “These aren’t a renewable source… removing them… means that wherever we take them from is permanently altered.”

Referring to seabed disturbance experiments dating back to the 1970s, she said: “You can still see the mining track down there really clearly. Where they remove the nodules, they don’t come back. The organisms that live there don’t come back.”

While some microbial recovery has been observed, she said full ecosystem recovery is unlikely within decades.

Sediment plumes: limited but uncertain at scale

Monitoring of exploratory crawlers suggests sediment disturbance may be more contained than initially feared.

“What scientists have found… is that there’s actually far less impact than we might have expected,” she said, explaining disturbed sediment rises “about five meters up” and that “98 percent falls within… 100 meters” of activity. However, she stressed commercial-scale machines could behave differently.

For midwater discharge, depth matters.

“It’s like finding a sweet spot of where you want to release sediment,” she said. “Below 1,500 meters is probably a good idea.”

Land mining comparison and human costs

Dr Pucko urged that ocean impacts be weighed against the environmental and social costs of land-based mining.

She cited copper pollution in Chile, nickel extraction in Indonesia involving “open-pit mines in the middle of a rainforest,” and cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where there are “extensive, documented examples of child labor.”

“It’s not just environmental harm that is a concern,” she said.

Regulation and legal uncertainty

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) has designated protected areas in the CCZ, with Dr Pucko noting it has “decided not to allocate about 30% of the CCZ to anyone” for conservation.

“Being strategic with regulation… is one of the main ways that we can really move forward with this and make the least amount of impact as possible,” she said. “There’s always going to be some impact… but to make the least impact as possible is maybe the goal.”

However, finalised international rules are still pending.

“Because the ISA has not come up with formal rules, there isn’t a UN-sanctioned regulatory structure for these companies to go in and start mining,” she said.

She described The Metals Company as “definitely the leader,” saying it is “utilising a U.S law… back in the 1980s to mine in international waters.”

On whether research is sufficient, she added: “Scientists are always going to say yes. We could always use more data. I think… these companies are going to move forward with or without that data.”

Pacific context and “dark oxygen”

On potential benefits for Pacific Island countries, she said agreements may include development funding, scholarships and scientific exchange.

“Some of these preliminary agreements, there’s money for development projects, there’s money for scholarships, there’s money for scientific exchange,” she said, though many figures “aren’t public.”

She also addressed the debated “dark oxygen” hypothesis.

“Dark oxygen is really interesting,” she said, but added that replication attempts “haven’t really been successful.” “It just feels too early to say for sure that that is what’s happening.” “There are conflicting results right now.”

A debate shaped by trade-offs

Dr Pucko concluded that both land and ocean mining carry consequences.

“Mining on land and in the ocean both have impacts that should be weighed against the environmental concerns, but also the human costs,” she said, describing the challenge as “trying to find a way to balance those ideas… with a world that needs minerals… to kind of advance cleaner, greener technology and limit climate change.”

Reflecting on her Pacific visit, she added: “I certainly learned as much from all the people I got to talk to as I hopefully got to share with them.”