By Jose Sousa-Santos

The recent seizure of more than two tonnes of cocaine in Fiji, and the arrest of four South American nationals allegedly linked to international trafficking networks, marks a meaningful shift in how Pacific Island states and communities are confronting transnational organised crime. While drug trafficking through the Pacific is not new, what is changing is the degree of local confidence, capability and ownership shaping the response.

For decades, Pacific Island countries have been treated by traffickers and, at times, by international partners, as passive transit zones: remote, lightly policed, and reliant on externally driven intelligence and enforcement. Fiji’s latest operation, which began in July 2025 in close liaison with the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA),suggests that these assumptions are increasingly outdated.

The importance of this seizure at Vatia in Tavua, in Fiji’s northwest, lies not only in the fact it was among the largest cocaine seizures Fiji has recorded in recent years, but in who was arrested. The apprehension of four Ecuadorians linked to international cocaine supply chains indicates that Fiji is no longer merely intercepting drugs at its own borders – it is beginning to penetrate and prosecute those within the networks.

Law enforcement operations in the Pacific have often ended once drugs were seized and local facilitators charged. Foreign organisers, financiers and logisticians typically remained beyond reach. This reflected limited intelligence ownership, jurisdictional constraints, and an understandable reliance on regional partners. In this instance, Fiji authorities were able to rely on stronger inter-agency coordination, improved intelligence handling, and a growing confidence to act independently rather than simply support externally led investigations. For an island state, that distinction matters. Control over intelligence determines whether a country sets priorities or reacts to events shaped elsewhere.

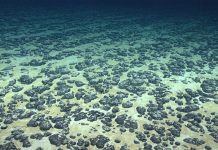

Recent discoveries of semi-submersible vessels in Solomon Islands waters underscore how Pacific routes are embedded in global cocaine supply chains.

This evolution in tactics has been swift. Fiji’s prosecution of those involved in a large-scale methamphetamine importation in 2024 sent a deterrent signal, even though no international figures were ultimately charged. But it also forced a reckoning within domestic institutions. Law enforcement agencies, including police and customs, began looking inward at corruption risks, insider threats and compromised units. Personnel were removed from sensitive positions, internal accountability strengthened, and professional standards reinforced.

The arrest of the four Ecuadorians suggests those changes are beginning to translate into real-world outcomes. For international criminal syndicates accustomed to operating with minimal resistance in the Pacific, the perceived risk environment is now shifting. However, none of this removes the enduring vulnerabilities that make the Pacific attractive to traffickers. Vast maritime zones, porous coastlines, abundant informal jetties, and limited patrol capacity remain defining features of the region. These challenges are compounded by economic pressures in coastal communities and the sheer tyranny of distance confronting enforcement agencies.

Recent discoveries of semi-submersible vessels in Solomon Islands waters, one of which reportedly contained an Ecuadorian voter identification card, underscore how Pacific routes are embedded in global cocaine supply chains. These are not opportunistic ventures but well-resourced, adaptive operations that view the region as both strategically valuable and vulnerable. Conventional border-control approaches alone will never be sufficient to counter them.

Pacific Island traditional leaders and communities are force multipliers in the fight against transnational organised crime. The region possesses a comparative advantage in its social and governance architecture. Initiatives such as Fiji’s Community Policing-Vanua-Multi-Agencies Crime Prevention and Maritime Security (CVM-CMS) pilot model are increasingly integrating traditional authority and governance – chiefly systems, churches, and customary land and sea owners – into national law enforcement frameworks. The aim is to empower community members to be the “eyes and ears at sea”.

When national institutions and traditional authority act in alignment, the combined effect is far greater than either could achieve alone.

By providing community leaders with direct, trusted communication channels to police and maritime authorities, these programmes convert local awareness into actionable intelligence. Fishers, villagers and chiefs are not expected to confront traffickers themselves, but to report anomalies quickly and safely: “Fishermen and women who spend hours at sea now have the opportunity to report suspicious yachts or illegal fishing activities to authorities for intelligence gathering and action.” The result has been earlier detection, faster responses, and broader coverage than formal agencies could achieve alone. As our research argues, this is a nascent Pacific maritime sentinel programme that can be replicated across the region.

This approach also addresses the social damage caused by illegal drugs. As narcotics penetrate Pacific communities, they generate shadow economies that undermine churches, chiefs and family structures. The visible willingness of traditional leaders to provide information and partner openly with authorities signals a critical shift away from fear and towards collective resistance.

At the launch of Fiji’s CVM-CMS pilot initiative in 2024, Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka called it a “whole-of-Fiji approach to preventing criminal and security activities arising on land or at sea”. Traditional leaders increasingly view this whole-of-society response to organised crime as their core responsibility as the impacts of drugs become more evident in their communities, from the corruption and distortion of village economies to the erosion of youth prospects.

This local ownership is essential. External partners can provide material assets, training and technical intelligence, but they cannot supply legitimacy. Trust and local leadership are critical force multipliers that must be generated internally. When national institutions and traditional authority act in alignment, the combined effect is far greater than either could achieve alone.

For the wider Pacific, Fiji’s experience offers cautious optimism. It demonstrates that island states are not condemned to vulnerability. Institutional reform, intelligence ownership and the deliberate mobilisation of traditional governance structures can meaningfully raise the costs of criminal activity. The cocaine seizure in Fiji is therefore more than a tactical success. It is evidence that the Pacific is beginning to fight back on its own terms, using its own strengths, and with growing confidence.