The Australia Institute says labour mobility schemes are worsening the health workforce crisis in the Pacific, with registered nurses and other skilled workers leaving for lower-skilled personal care jobs in Australia and New Zealand.

The report says “labour mobility is a significant contributor to Pacific Islands’ economies,” but warns the expansion of temporary migration schemes into aged care has led to the loss of skilled health workers from Pacific Island countries.

It says workers on temporary visas “are vulnerable to being underpaid and exploited, due to their visa status” and calls for reform of labour migration systems and stronger consultation with workers.

Fiji continues to face major labour market pressures. The report notes the country’s population of about 930,000 is growing and has potential for economic gain, but unemployment and participation rates show deep gender gaps. Women’s labour force participation is 36 percent compared to 77 percent for men, and one in five young people are not in employment, education or training.

The minimum wage rose to FJ$5 (US$2.50) per hour in 2025, but over 40 percent of employment remains informal.

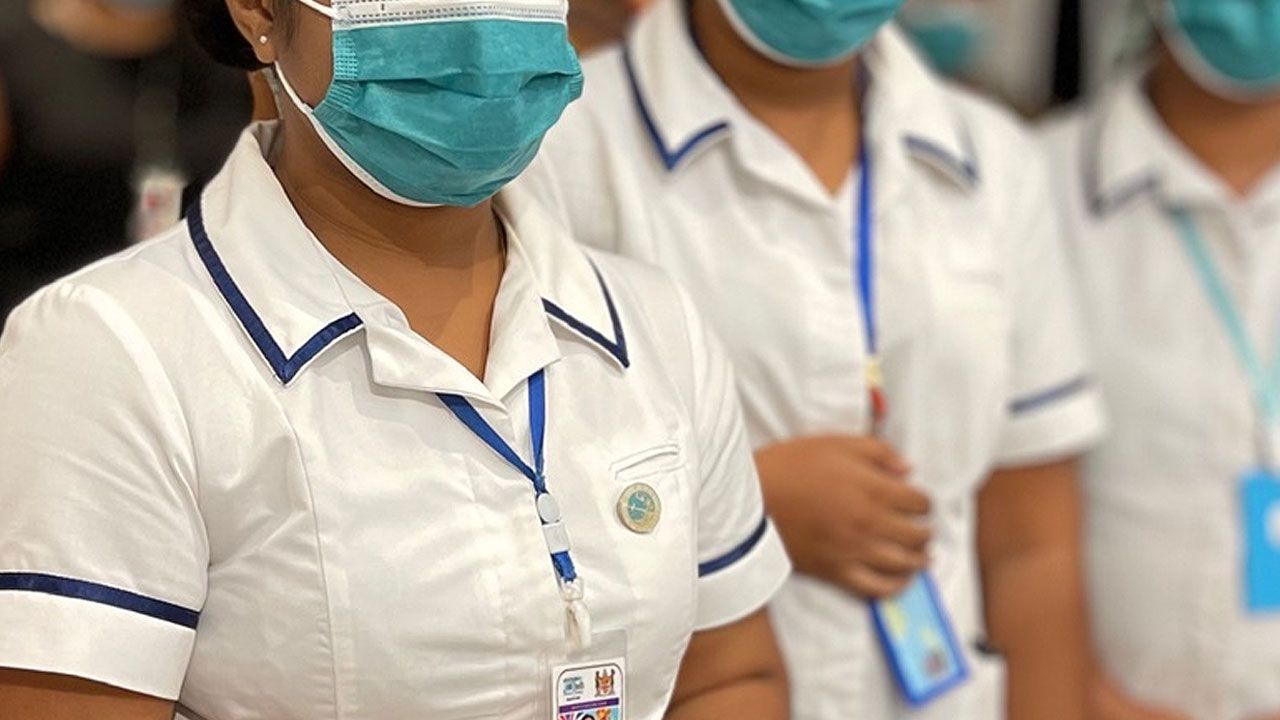

The report says Fiji underinvests in health care, especially primary health care. It highlights high levels of non-communicable diseases, which caused 68 percent of deaths in 2021, and notes that “access to quality health care is a serious problem.”

Fiji meets the WHO minimum threshold of skilled health workers, but the report says this may underestimate what is actually needed.

Between 2018 and August 2023, about 80,000 Fijians left the country “for better employment opportunities and emigration.” The government estimates more than 50,000 left between July 2022 and December 2023 alone.

The number of Fijians in Australia jumped from 13,470 in 2022 to 22,599 in 2023, with work visas doubling. In 2023, remittances were 9.2 percent of Fiji’s GDP.

Participation in the PALM scheme grew sharply after COVID-19. In July 2025, there were 5,340 Fijian workers in Australia under the scheme, mostly in agriculture and meat processing. Just 4 percent were in health care and social assistance.

Student visa numbers also rose. In 2024, 5,665 Fijian students were studying in Australia.

To cope with the exodus of skilled staff, Fiji increased the retirement age twice, extending the service period for specialists in scarce skills areas.

Health workers and unions told researchers that public hospitals are losing staff to emigration and to private hospitals within Fiji. They say this is undermining patient access and confidence in the public system.

Workers report rundown facilities, shortages of trained staff, and a lack of equipment or training to operate new equipment. At Fiji’s only mental health hospital, St Giles, conditions were described as dire.

The report highlights unsafe staffing levels, with too few experienced nurses to supervise junior staff. Senior workers said the loss of mentors is “highly damaging to current and future health system capacity.”

Unions say disrespect towards health workers is widespread, including delays in allowances owed since 2018 and a lack of professional support.

Workshop participants say labour migration must support, not weaken, Pacific health systems. They called for transparency about emigration, stronger regulation of recruitment agencies, and union involvement in pre-departure briefings.

They also want strategies to retain health workers in Fiji and help reintegrate them when they return from labour mobility programs.