Analysis by Professor Jon Fraenkel

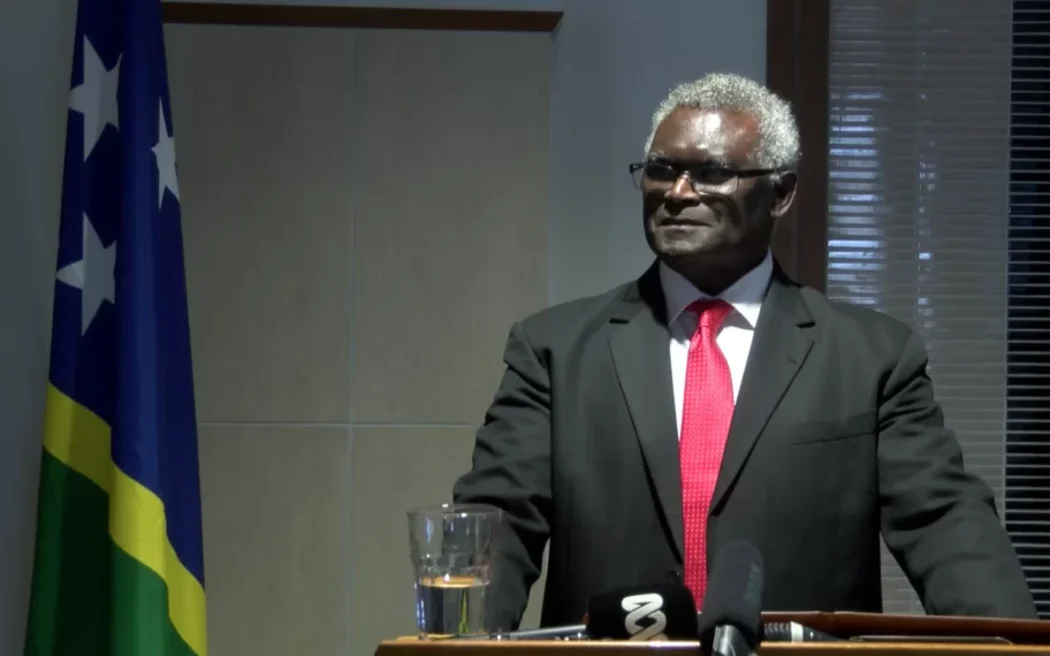

In the Solomon Islands, an election in April will decide whether a Chinese allied prime minister keeps his job. Manasseh Sogavare has taken advantage of urban unrest in the past, but his security partners may be reluctant to assist in future.

The Solomon Islands goes to the polls in April 2024. This will be the first election since the country switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China in 2019 and then signed an April 2022 security deal with Beijing. The leaked draft version of the deal gives Chinese security personnel access to the country and potentially allows China to “make ship visits” and deploy forces “to protect the safety of Chinese personnel and major projects.” Alarm bells have been ringing in Canberra, Washington, and Wellington ever since.

Heading into the election, the incumbent prime minister, Manasseh Sogavare, is in pole position, now backed by Chinese financial support and facing a weak and divided opposition. Many observers in Australia and New Zealand expect him to be re-elected, or even to steal the election and then to strengthen his alliance with Beijing. Yet, no previous prime minister has gone into a general election and then re-emerged as the country’s leader. If Sogavare succeeds in returning as head of government after the polls, he would become the first Solomon Islands politician to achieve this.

Sogavare has served as prime minister four times, but never for consecutive terms. He has a penchant for wacky money schemes and a reputation for instrumentalising disorder to serve his own political purposes. When he speaks publicly on the campaign trail, he shouts like a 1970s British trade unionist turned tub-thumping preacher.

Sogavare first secured the top job in the wake of a coup. Over the course of 1998-2000, an uprising on the island of Guadalcanal drove settlers from the neighbouring island of Malaita out of the rural parts of the island and into the capital, Honiara, which is also on Guadalcanal. In retaliation in June 2000, a militia group called the Malaita Eagle Forces – in collaboration with the paramilitary police force – overthrew the elected government and installed Sogavare as their puppet. During his initial 17 months in charge, militants were in control of Honiara, the treasury went bankrupt, and GDP shrank by around 25 percent. After an election in December 2001, he was replaced by Sir Allen Kemakeza. Sir Allen was the prime minister that invited Australia to send troops and police into the country in July 2003.

Sogavare returned as prime minister in 2006 after another major crisis. An election in April of that year triggered a major riot in the capital, which Australian-led Regional Assistance Mission (RAMSI) police personnel were unable to quash. The government collapsed. By playing off rival camps against each other, Sogavare got himself elected as replacement prime minister, and during this second stint in office, relations with Canberra badly deteriorated. An Australian High Commissioner was declared persona non grata. After Australian police officers serving with RAMSI kicked down the door of the prime minister’s office in a search for evidence of illegal activity, the Australian Police Chief was also expelled. In October 2007, Sogavare’s Foreign Minister Patteson Oti denounced the Australian “occupation” of his country at the United Nations General Assembly in New York. Fraught relations with close neighbours came at a price. Sogavare was ousted by his own parliament two months later, partly due to disagreements with other Pacific Islands leaders about his stance on RAMSI.

During Sogavare’s third stint in office (2014-17) he cultivated closer relations with Australia, pressing for the enactment of anti-corruption laws and for the establishment of an independent anti-corruption commission. Resident foreign diplomats naively concluded that he had dropped his earlier anti-Australian stance. But RAMSI was in its withdrawal phase ahead of the end of the mission in 2017 and it was no longer as intrusive as it had been in 2006. Sogavare calculated that his political survival was better served by cordial relations. Ironically, it was a cabinet rebellion over the anti-corruption bills that led to his defeat in a no-confidence vote in November 2017.

Sogavare became prime minister for a fourth time after the April 2019 polls. Following the diplomatic switch five months later, a showdown ensued with Daniel Suidani – the premier of Malaita province – who strongly opposed the new alliance with “Communist” and “atheist” Beijing. Malaita is the country’s most heavily populated island. Descendants of migrants from Malaita also account for the lion’s share of the Honiara population, many of whom inhabit the “leaf house” and corrugated iron squatter settlements to the east of the capital. Sogavare was once the hero of these urban Malaitans. Yet it was Malaitan protests against his government that triggered major riots in Honiara in November 2021. The Chinatown district was burned to the ground. There was an arson attack on the prime minister’s family residence. This is what precipitated the signing of the 2022 security deal with China. Ever since, a handful of Chinese police have been stationed in Honiara. In reaction, the post-RAMSI Australian bilateral police presence has been extended and enlarged at least until after the election.

Sogavare was able to defeat his pro-Taiwan opponents on Malaita partly due to declining American enthusiasm for the sub-national rebellion. Suidani was ousted in a vote of no-confidence in the Malaita Provincial assembly in February 2023 that was orchestrated by the national government. Bribes were exposed. Despite his dwindling support in Malaita and in eastern Honiara, Sogavare has been able to retain the backing of most of the Malaitan MPs in the 50-member parliament.

Sogavare may have gained control of the prime ministerial portfolio four times, but his inability to do so for consecutive terms reveals a critical feature of Solomon Islands’ politics. Melanesian politicians are wary of allowing leaders to accumulate too much power. Prime ministers face constant difficulties trying to keep rebellious MPs on side. To do so, they must often dish out money, which is why the anti-corruption commission that Sogavare pressed for across 2016-17 has languished without funding.

Chinese cash may have assisted Sogavare in surviving a no-confidence vote in 2021, but after a general election he will be less secure. After all, any of the MPs on the government side could be beneficiaries of Beijing’s largesse. Key government critics, such as Matthew Wale and Peter Kenilorea, will be so desperate to avoid another term in opposition that they would team up with any ambitious minister to get into government.

There is no evidence that Sogavare deliberately orchestrates disorder for personal advantage, but he has been able to use urban disturbances to meet his political goals, both after 2000 coup, following the 2006 riots, and to justify the deal with China after the turmoil of 2021. If further disturbances ensue after the April election, he will no doubt look for support from both Chinese and Australian police, but Canberra will not collaborate with Beijing operationally, while the small present-day Chinese police contingent will be wary of the dangers of deployment on the streets of Honiara (No one knows whether immunities from local prosecution have been obtained). The easier option may be to let the rioters run amok, which is basically what happened east of the Mataniko bridge during the riots of November 2021. If so, Sogavare may be no longer be master of the mayhem that so regularly afflicts his country.