Women’s bodies should not be held captive to choices made by governments or individuals, the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) has said, as it launched its flagship State of the World’s Population Report for 2023.

Instead of instituting these measures, policy and law makers must work to empower women to achieve their individual reproductive goals.

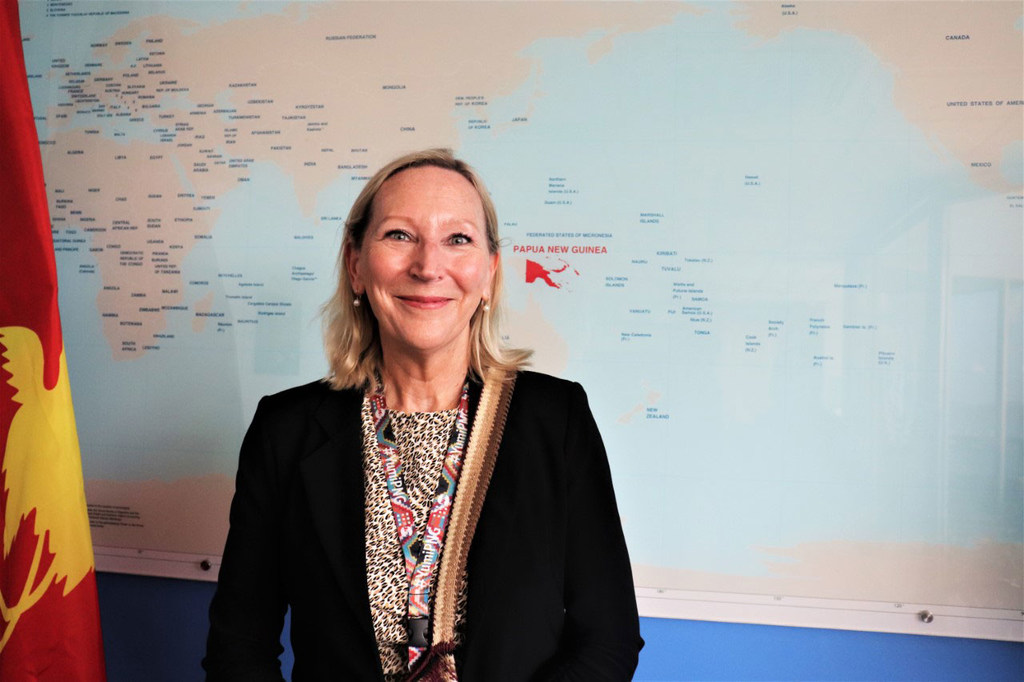

Speaking to UN News, Marielle Sander, the Fund’s Resident Representative in Papua New Guinea, explained why the current global population of 8 billion marks an opportunity for a broader conversation on how to make reproductive choices simpler for families and women.

UN News: With the global population now at about 8 billion, are countries around the world worried about the population rates, and if so, does this result in policy decisions that affect women?

Marielle Sander: The UNFPA State of the World Population Report for 2023 addresses the question of the 8 billion globally. Many countries are having different reactions because some are facing a decline in fertility whereas others are worried about their population.

We see this as an excellent opportunity to have that conversation and to reassure countries that there need not be a knee-jerk reaction. We need to look at evidence and data to assure everyone that there’s room for everyone, but we need to plan better.

That is part of the solution. Historically speaking, every time countries have tried to enforce a policy related to fertility, there has been a backlash. So, the solution to our problem is always to look at how to make choices more simple, for families, for women.

The worst thing we can do is decide that women should have no control over their reproductive rights.

UN News: Looking at the global picture, were there funding decisions made during the COVID-19 pandemic that affected women?

Marielle Sander: During COVID-19, we saw a severe risk restriction on services for women. Most countries shut down all essential or non-essential services; family planning, access to HIV antiretroviral drugs or keeping a birthing unit labour ward open were not top of mind. As a result, we’ve seen a larger number of babies being born. We see this in Papua New Guinea now.

We also see the negative effects of COVID-19 in terms of increased levels of family violence and usually, the family support centres that provided counselling and support to women had been, in those situations, shut down or repurposed to address the coronavirus pandemic.

UN News: Do you think there could be an element of gender discrimination?

Marielle Sander: There is an element of gender discrimination in how we look at services and sometimes policies and how it’s so easy to forget women and what they need to stay healthy and also in terms of a well-functioning society,

UN News: What are the main challenges in Papua New Guinea?

Marielle Sander: The challenge is that we haven’t had a census for quite some time, so the total size of the population has been debated, sometimes heatedly. It’s clear that the population is above 9 million and the concern for the government is the ability to provide services. Most of the population is based in rural areas, where services need to be.

However, many health-related services are in urban centres. There needs to be a rethinking about how reproductive health services and family planning life-saving services can be taken into the most remote areas, and that’s not an easy thing to do.

UN News: What happens to women in Papua New Guinea if they do not have access to the type of services you’re describing, particularly in remote areas?

Marielle Sander: Papua New Guinea, it’s one of the most mountainous, but also most exciting and very remote countries in the world. Sometimes, it takes days to walk to one health facility and the capital city, Port Moresby, is still not connected to the rest of the country. You either have to fly or go by boat.

I just came back from a mission in the highlands in a remote community where 100 women were waiting for the mobile clinic that we’d set up. I think 10 or 20 were pregnant.

One story particularly affected me because it was about a woman who had had to give birth by herself in the middle of the night because the health facility had been shut down. She was crying as she recounted the story in front of everyone.

She said “I had to give birth to the baby. I had to cut the umbilical cord. I had to do everything, and I didn’t know at one point whether I was going to live or die.”

These are the stakes in rural Papua New Guinea. If you don’t have access to these services, there is a high risk that you might die. Currently, the demographic health data tells us that 171 out of 100,000 women in Papua New Guinea die as a result of labour, but the actual figure is probably closer to 500 because the 171 was just based on the data from the health facilities.

So, there are many challenges in a country like this, which is why it’s important for us to think about how we can make life easier for community health workers and for health service providers to access the women and those who need help the most.

Another one of the key challenges is there are not enough health workers in Papua New Guinea. If we look at midwives, we have less than 800, even though for the size of this population, we need 5,000. Midwives are important because they are the ones that provide counselling to women and men too.

Generally speaking, women here are more comfortable talking to another woman. The midwives provide expert advice on family planning and also are there to support women during labour. They can also provide couples counselling around fertility or infertility.

So, we’re missing essential service providers who are experts in the area of sexual and reproductive health in a country that really needs specific assistance to address this problem.

SOURCE: UN NEWS CENTRE/PACNEWS